The Guerlain Griffon

Craig Koshyk

In 1907 Robert Leighton wrote about an orange and white rough-haired breed known as the Guerlain Griffon. He described it as:

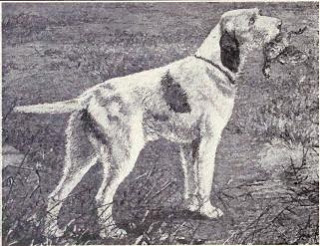

...perhaps the most elegant in shape and appearance, owing to its shorter and less rugged coat and lighter build. This breed is usually white in color, with orange or yellow markings, rather short dropped ears, and a docked tail, and with a height of about 22 inches. The nose is always brown, and the light eyes are not hidden by the prominent eyebrows so frequent in the French spaniels.

W. E. Mason also mentions the breed:

This is a medium-sized dog, short in the body and compactly built. He has a big head for his size and the eyes are rather large and light-brown in color. The nose is always brown with nostrils well open. Chest broad and back strong and well-developed. The legs are straight and muscular, rather on the long side and well-covered with short, wiry hair. Stern [tail] is carried straight, covered with wiry hair but without feathering, and a third of its length is generally docked. The coat is hard and wiry, rather short and not curly.

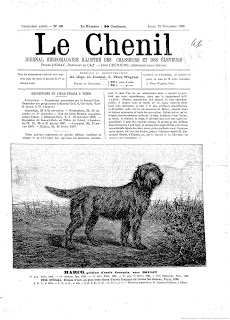

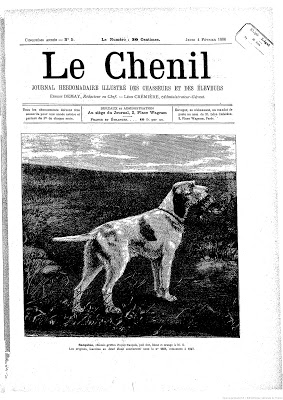

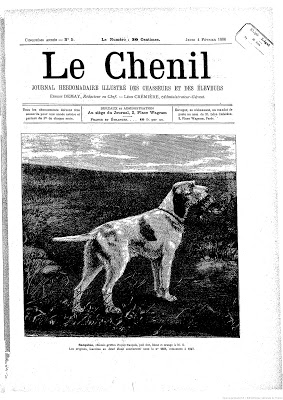

The most interesting document I have found on the Guerlain Griffon is an article published in the February 4, 1886 edition of Le Chenil. It was written by the Marquis of Cherville (Gaspard de Pekow) and describes his own efforts to establish the breed that was later perfected by a man he refers to only as “Mr. G”.

The Marquis wrote that he purchased a brown and white rough-haired griffon from a Mr. Lebastard in 1846. He named the dog Tom, and became so fond of it that a short while later he bought a bitch with a similar coat in Normandy. However, when he bred the two together, he found that the results were not what he had hoped for. The offspring had long, silky hair. They were also smaller than their parents and much less vigorous. So, in 1857, the Marquis bred a bitch named Crimée, a perfect hunter but with mediocre looks, to an extraordinarily vigorous Pointer named Narbal. From that union, he kept two pups: a dog he named Garçon and a bitch he named Cartouche.

When Cartouche was a year old, the Marquis gave her to Alexander Dumas, the well-known author of such classics as The Count of Monte Cristo and The Three Musketeers. Dumas did not keep Cartouche; he presented her as a gift to the national hero of Italian unification, Giuseppe Garibaldi. Naturally, this created a huge demand for her puppies in Italy, and she was bred several times leaving many descendants.

Garçon, Cartouche’s brother, had a harsh, fawn-colored coat with white “socks” on all four legs.

He was very tall, with incredible physical strength. I once saw him in front of M. Clérault, retrieve at a gallop a hare of seven or eight pounds and, despite the weight, he leaped over a stream a meter and a half wide in a single bound.

The Marquis repeated the breeding that produced Garçon and Cartouche. From it, he kept a bitch. He named her Mike. But Mike’s coat was mainly white with only small fawn-colored patches and spots. Nevertheless, the Marquis was so pleased with Garçon and Mike—he wrote that they were the best hunting dogs he’d ever known—that he decided to establish his own line by way of a brother-sister mating.

The Marquis repeated the breeding that produced Garçon and Cartouche. From it, he kept a bitch. He named her Mike. But Mike’s coat was mainly white with only small fawn-colored patches and spots. Nevertheless, the Marquis was so pleased with Garçon and Mike—he wrote that they were the best hunting dogs he’d ever known—that he decided to establish his own line by way of a brother-sister mating.

In the article, which is written in French, he actually uses the English expression “in and in” to describe his breeding program. However, he admits that things did not pan out the way he had hoped. After the third generation, everything seemed to fall apart. The dogs were smaller and lacked vitality. Many fell ill, some were timid and others had little to no hunting abilities. Realizing that he was getting on in years, and no longer having the time to continue his projects, he stopped breeding his griffons and turned to English dogs instead.

This is where “Mr. G” enters the story. His full name was Aimé Guerlain and he was the son of Pierre-François Pascal Guerlain, the founder of one of the oldest perfume houses in the world. Aimé Guerlain was also an avid hunter who spent many days in the marshes of Picardy, particularly near Le Crotoy, a spa his father established in the early 1800s on the Bay of the Somme.

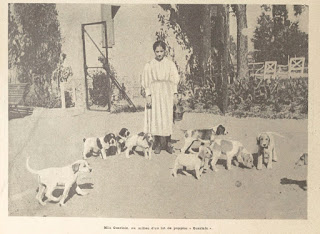

Their search, without being too wide, is very active and sufficiently open; they have a good nose and their points are very solid; they are remarkable for their prudence and cooperation. Well-trained, they are exceptional retrievers. Overall, Mr. G, and M. Boulet, in their breeding of griffons, demonstrate a steadfastness, a tenacity that we must applaud and from which their breeds will benefit greatly if these men can create converts from among their colleagues.

When the first field trial was held in France in 1888, the winner of the quête restreinte (close search) stake was a Guerlain Griffon named Sacquine. Sadly, despite this and other achievements —Aimé Guerlain even sent a number of his dogs to Tsarevich (Grand Duke) Nicholas of Russia — he was unable to gain many converts beyond the circle of his close friends. The Guerlain Griffon eventually died out just after the turn of the 20th century.

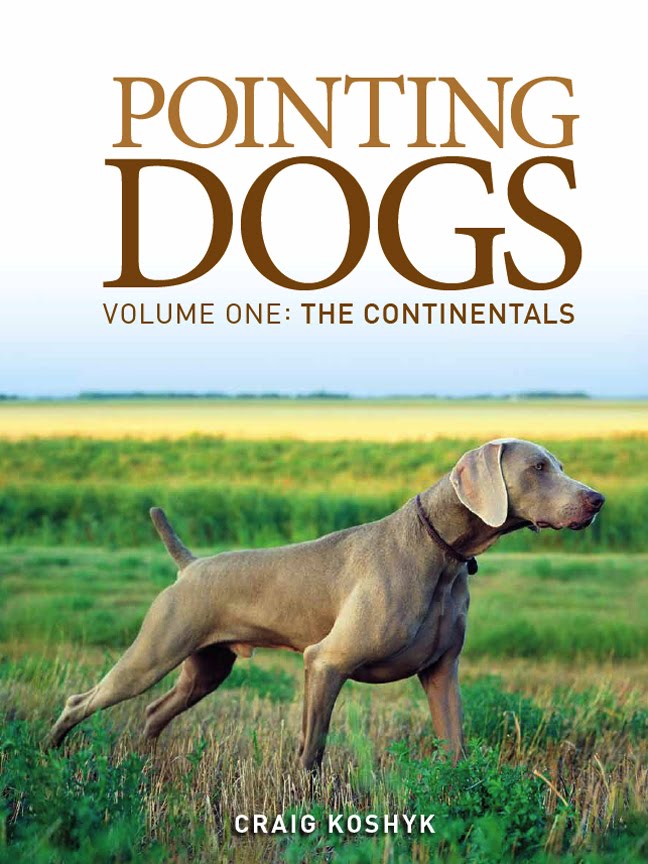

Read more about the breed, and all the other pointing breeds from Continental Europe, in my book Pointing Dogs, Volume One: The Continentals

Read more about the breed, and all the other pointing breeds from Continental Europe, in my book Pointing Dogs, Volume One: The Continentals