The Braque Dupuy

Craig Koshyk

The origins of the Braque Dupuy have been the subject of speculation

since it first appeared on the French gundog scene in the mid-1800s. No

one knows exactly how the breed came to be, but it was probably created

by hunters who bred sight hounds to French braques.

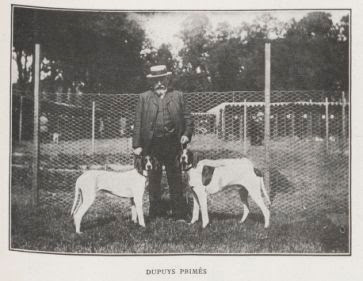

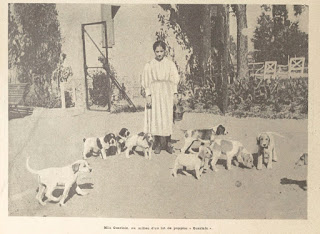

The first such crosses are said to have occurred in 1808 at the kennels of Omer and Narcisse Dupuy, hunters in the Poitou region of France. Apparently the Dupuys were impressed by the hunting skills of a sighthound named Rémus belonging to one of their friends. They were also frustrated with their own braques. They found them to be too heavy and close-working. So, in an effort to develop a dog with the speed of a sight hound and the firm point of a braque, the Dupuy brothers bred Rémus to two of their bitches. Three pups from the first two litters were kept and then bred back to their best braques. That second cross produced a dog with all the qualities they were seeking. They named him Rémus in honor of his grandsire, and bred him to a female braque named Léda. Pups from that breeding were the first to be considered true Braques Dupuy.

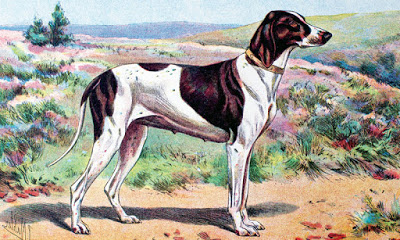

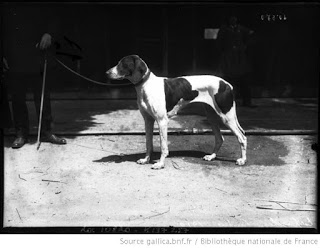

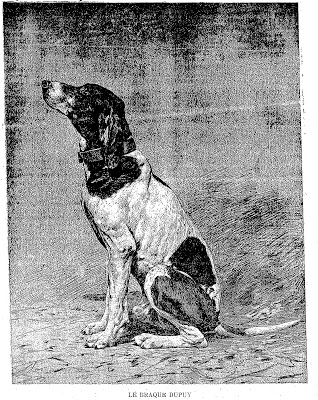

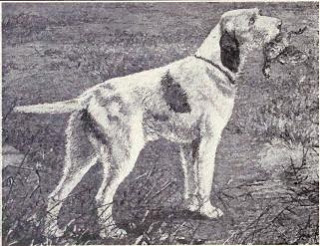

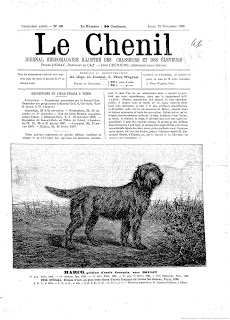

The breed struggled to gain acceptance in its early days, and by about 1850 was in serious trouble. But a man named Gaston Hublot is credited with reconstructing it and even wrote a book about the breed, Le Chien Dupuy, in 1899. In terms of appearance they resembled sight hounds more than braques. They were very tall and had a short white and liver coat. Some may have had black and white coats.

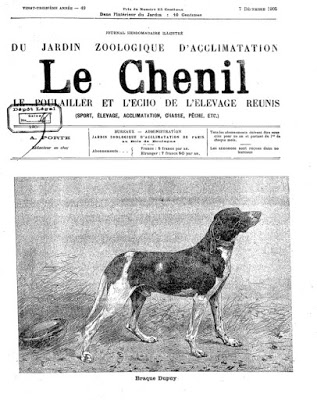

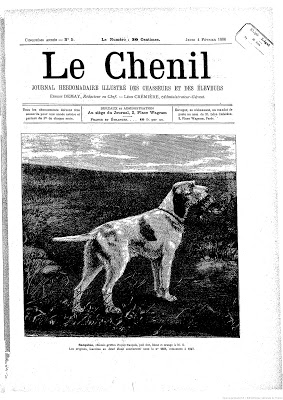

In terms of hunting style there seems to be a difference of opinion. Some authors describe the Dupuy as a fast dog that excelled at hunting on the plains. Others write that it was more of a trotter. In a letter published in Le Chenil in June of 1887, a Mr. O. Pineau, who had been around Braques Dupuy for most of his life, explained that it may have been a bit of both.

My friend Christophe Oriou, an avid hunter and field trial enthusiast, lived in the Poitou region in the 1990s. While there, he did some research into the breed.

The first such crosses are said to have occurred in 1808 at the kennels of Omer and Narcisse Dupuy, hunters in the Poitou region of France. Apparently the Dupuys were impressed by the hunting skills of a sighthound named Rémus belonging to one of their friends. They were also frustrated with their own braques. They found them to be too heavy and close-working. So, in an effort to develop a dog with the speed of a sight hound and the firm point of a braque, the Dupuy brothers bred Rémus to two of their bitches. Three pups from the first two litters were kept and then bred back to their best braques. That second cross produced a dog with all the qualities they were seeking. They named him Rémus in honor of his grandsire, and bred him to a female braque named Léda. Pups from that breeding were the first to be considered true Braques Dupuy.

The breed struggled to gain acceptance in its early days, and by about 1850 was in serious trouble. But a man named Gaston Hublot is credited with reconstructing it and even wrote a book about the breed, Le Chien Dupuy, in 1899. In terms of appearance they resembled sight hounds more than braques. They were very tall and had a short white and liver coat. Some may have had black and white coats.

The Dupuy Pointer is a big upstanding dog with considerable elegance in his movements. The head is narrow and long. Occipital bone prominent, muzzle long, lean and slightly arched. Eyes golden brown in color with a rather melancholy expression. … Stern [tail] long, set low and carried like a greyhound’s tail.

The Dupuy has a lot of drive; when young and rested it searches at a gallop; if it is affected by age or fatigue, its pace is a fast trot. In action, it holds the head high, into the wind, but when a partridge runs, it follows all the twists and turns of its trail, sometimes putting its nose where the game placed its feet. The Dupuy retrieves quail or partridge naturally when he has seen other dogs do it. But the use of the force collar is often necessary to make it retrieve a hare that it finds a bit heavy, or strong smelling waterfowl that it is not used to.In another account, the breed is described as being similar to the English Pointer.

The Braque Dupuy is very much like the English Pointer in build, but his head is squarer, and he is stouter on his pins [legs]. He is a moderately fast ranger, and a clever finder of game, very stanch and steady. When brought-up to it he does not mind rough work, but few of them go well to water. They are dashing workers, and are very greatly prized. I have seen a brace that would come to their points at awful distances, by a tropical heat; hence, for the hot departments of France they are admirably suited. (Walter Esplin Mason, Dogs of All Nations, 48)After the First World War, the Braque Dupuy went into a steep decline, and had all but disappeared by the 1950s. In 1960, Jean Castaing wrote:

If, here and there, we see, very rarely, a dog called a Braque Dupuy, it is most often a bastard of unknown origins whose sighthound look is more or less of the Dupuy type. I do not believe that there is an organized breeding program even though breeders try from time to time to reconstitute this artificial dog that had its moment of glory mainly due to a desire to create a French version of the [English] Pointer.

My friend Christophe Oriou, an avid hunter and field trial enthusiast, lived in the Poitou region in the 1990s. While there, he did some research into the breed.

I discovered that the last Dupuy with a real pedigree belonged to Mr. Charpentier, a dentist in the village of St. Jean de Sauves. His wife showed me some color photographs of the dog—it had died in 1964. It was very moving to realize that I was looking at the very last Braque Dupuy. After him, the breed disappeared without a trace!Strangely, despite that fact that no one has actually bred a Braque Dupuy in over half a century, the FCI continues to publish the breed’s official standard and still lists it in Group 7 for pointing dogs. There are even people in Europe qualified to judge the breed—even though they have never seen a Braque Dupuy! But there is a logical explanation for this seemingly bizarre situation. It was Michel Comte, the father of the modern Braque du Bourbonnais, who explained it to me.

Under certain circumstances, a breed that is thought to be extinct can still be listed. It is a way of “keeping the porch light on”. In other words, if someone decides to revive the breed from whatever remnants can be found, there will still be an official standard to use as a guide and there will be judges ready to evaluate the dogs. In fact, if it were not for this peculiar policy of the SCC, the Braque du Bourbonnais would have never been recreated.