An American in France.

Craig Koshyk

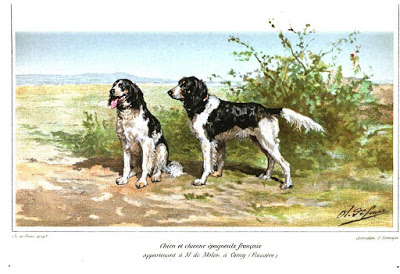

Bill Kelley is a man on a mission. The goal of his Cache d'Or Bretons kennel is to produce Epagneul Bretons (French Brittanies) in the United States equal to the finest found in France. So, every year he travels from his home in Maryland to France to learn about the breed, run his dogs in typical French terrain, walk with judges at field trials and learn about the finer points of conformation from the best show judges in the country.

As a fellow francophile, I have much in common with Bill. I've spent a lot of time in France watching French dogs do their thing. But I've never actually met an American there or spoken to one that has dedicated so much time learning about the French system. So I was interested to hear Bill's thoughts about the French field trial scene and the dogs they produce and asked him a few questions.

Can you tell me how an American such as yourself got involved with field trials all they way across the ocean? After forty years of pointing dogs, I decided to get my first Epagneul Breton. At that time, I didn't even know that a French Brittany was an Epagneul Breton! Like a lot of people, I was attracted to the "close-working" gun dog- and the tri-color coat. I wanted an orange/white female and the breeder (Kevin Pack at Carolina Brittanies) only had a black/white male. I took him. So glad I did. When I looked at Cache's (Vulcan du Talon de Gourdon) pedigree, I noticed their were lots of red letters for champions. Having started my bird dog life in AF horseback trials with an English Setter, I knew what our field champions did, but had no clue as to what champions in France were required to do. The more I researched, the more I realized the only way to understand was to go to France and see for myself.

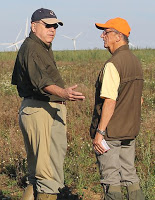

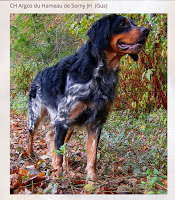

I have been fortunate since my time in the breed to have some very fine mentors, chief among them is Pierre Willems, former member of the CEB France committee and owner of the world-famous Hameau de Sorny kennel. Through Pierre, I made my first trip to France more than a decade ago. I was permitted to walk the trial with Judge Jean Moussour. Understand, in French trials, there is no gallery as one would see in the US. Only the judge, landowner's guide, and handler are typically in the field.

Several days in the winter wheat of Vimpelles showed me I knew very little of what an EB was made to do- BUT I was anxious to learn! I did not know it then, but I was watching some of the finest EBs ever to hit the ground in France. The hunting and pointing was intense. The rules were formidable and unforgiving. It was a real challenge- and one that I believe has helped form the EB into the breed it is today.

Tell me about your first experience(s) there, what was it like to compete in such a different scene and how steep was the learning curve? My experience in French FTs has been limited to walking with judges. I have entered one of my dogs in a TAN in France (which in my observation is significantly different than those run in the US. see below.) We did well, passing the TAN and being recognized by the judge, a top French trainer/handler, as "the best dog I've seen today." In the French system, part of a judge's training is to work side-by-side with a judge. In terms of learning, this is far better than running a dog.

A handler get to only see their dog. When one is with the judge through the day, you have the opportunity to learn the intricacies of the rues and what a judge wants to see. Through the years I have had the privilege of walking field trials with several of the top judges in France. Each time is a wonderful experience. These judges are real dog men. They understand the demands of a working breed and the needs of the hunter who walks behind the dog.

A handler get to only see their dog. When one is with the judge through the day, you have the opportunity to learn the intricacies of the rues and what a judge wants to see. Through the years I have had the privilege of walking field trials with several of the top judges in France. Each time is a wonderful experience. These judges are real dog men. They understand the demands of a working breed and the needs of the hunter who walks behind the dog. Dog people are dog people, no matter the language or culture. I am fortunate to have some fluency in French, so that has been helpful. However, the common bond of loving good dogs and good dog work transcends any possible divide. The learning curve was steep at first, has smoothed out a bit, but I am still learning. What I have found is summer up in a saying one of my mentors has used- "When the student is ready, a teacher will be found." What wisdom. It's all about our willingness to learn. EVERY person I have met in the French dog world has been exceptionally welcoming and willing to share. It has been an amazing relationship.

What are some of the most important (or interesting or both) things you've learnt about field trials in Europe? The most interesting thing I've learned is that just as in the US, there is no such thing as "a field trial." While all the French/FCI trials are on foot, the game and terrain are as varied as Europe itself. While the typical trial in France is the spring trial in winter wheat on wild partridge, there are equally popular autumn, shoot to retrieve, trials on released pheasants. There are also niche trials on wild snipe, woodcock, and mountain birds. Each has its unique requirements of both dog and handler. FT in France are serious business. Most dogs are handled by professionals whose livelihood depends in the success of their dogs. In addition, there is a circuit of trials held several days each week, not just on weekends. Dogs that come through this process successfully certainly have proven their merit for future breeding.

Overall, I find that the American EB community's attitude can be summed-up in a quote from one of their club officer's at the CEB France National show several years ago- "I came all the way to France and I didn't learn anything." See the quote above about a "ready student." Within the past month, two officers of the US club have gone to France and run one of their dogs. Hopefully, they were "ready students." I often hear people talk about how much they love the EB. I wonder if they understand the process (the French process) that created the breed they love. I fear that like many other things, the realities of time and distance lead to changes and alterations from the original . The expectations are different here - lower, in my opinion. I have seen US EB TANs and trials. What goes here would never go in France. For example, I saw an EB run a TAN here. After two attempts to find scent, the dog was put on a check-cord and handled onto the bird. It flash-pointed for a moment and moved on. It passed. This would never go in France.

As for myself or others competing in France, I think most Americans are simply uninterested. We tend to be be quite provincial and think that our styles, systems, and ways are superior to others around the world. Unfortunately, I am afraid this attitude will lead to the diminution of the breed. I am convinced that if we want to maintain and improve the quality of the EB in the US, we MUST have a stronger relationship with our firends in France. After all, they are the creators and guardians of the breed.

What are some myths about the european field trial and hunting scene that you've had to dispell? The best way I can sum up the"myths" of the French hunting scene is to recount my landing at Charles de Gaulle Airport on my first trip to France. As we descended, all I could see were fields and woods. Little villages and towns, here and there, but mostly green. Where did Paris go? What happened to the Eiffel Tower? Like most folks, I think, my perception of France was a busy, urban, cosmopolitain place. It is that, of course, but so much more.

What are some myths about the european field trial and hunting scene that you've had to dispell? The best way I can sum up the"myths" of the French hunting scene is to recount my landing at Charles de Gaulle Airport on my first trip to France. As we descended, all I could see were fields and woods. Little villages and towns, here and there, but mostly green. Where did Paris go? What happened to the Eiffel Tower? Like most folks, I think, my perception of France was a busy, urban, cosmopolitain place. It is that, of course, but so much more.The landscape of France is vast and agrarian. The land is much more covered with field and woods. Spawling development in contained. Places to hunt, while typically organized for hunting clubs abound. Wild game, at least as compared to Eastern US, is abundant. Many French people hunt - and it is an important part of their culture. It is important to remember that for centuries hunting was the privilege of the ruling class. Poaching was a possible death sentence. Somehow, it appears that the French still understand these roots of our sport and strongly resist efforts to change the traditions they've developed. Mind you, neckties are not required when hunting in France as in the UK, but the French hunting traditions are strong. Frenchmen are proud to show you their Darnes and take you to the sporting goods stores. As you can tell, my appreciation for and affinity with the French culture is strong. I've learned a lot from my French friends and my life is richer for the experiences and relationships.

My best advice for any American who loves their EB and wants the breed to prosper is to get over their fears and insecurities about the langauge barrier and visit France, see their trials, and shows, and get to know the wonderful people responsible for giving us the dogs we love so much.

Enjoy my blog posts? Check out my book Pointing Dogs, Volume One: The Continentals