SELECTION AND BREEDING

Approximately 550 Weimaraner pups are whelped in Germany each year, almost all of them bred by and for hunters. There are probably close to twenty thousand Weim pups born every year in the rest of the world. Unfortunately, 90% of them are from non-hunting lines.

Field-oriented breeders in North America tend to put more emphasis on speed, range and point than their German counterparts. Retrieving and water work are also very important for North Americans, but blood tracking and predator sharpness are generally not given much consideration. US and Canadian “field-bred” Weimaraners are often slightly smaller, faster and may be wider ranging than their relatives from Germany. In terms of appearance, they usually lack the extreme angulation of Weimaraners from show lines.

Aline Curran, an American Weimaraner breeder with US-bred and German-bred dogs, describes the differences between them:

My German dogs have more drive, more focus. They are bolder, more hard-headed, WAY more intelligent, and did I mention DRIVE? My American dogs from field lines have more style. They are faster and wider ranging, more eager to please, softer, more hyper, and did I mention STYLE? I find the German dogs easier to train, but harder to keep trained. They are very strong-willed and scary-smart. If you don’t stay on top of them, they will find very creative ways of getting away with murder. The Americans, on the other hand, are very eager to please, but don’t catch on as quickly. They are soft, so you can’t rush their training or you will lose the style, which is their best asset. Once they are trained, they stay trained with only gentle reminders.

While it is reasonable to assume that over the last 100 years the Weimaraner has been bred to fairly high levels of purity, rumors persist that crosses to other breeds have occurred. Only one story can be confirmed. During the 1960s, there was a short-lived, and rather divisive program in Germany where a few Weimaraners did in fact receive “outside blood”.

According to a former president of the Weimaraner club, Dr. Werner Petri, a small group of breeders crossed English Pointers and Weimaraners in the early ’60s in an effort to establish a new breed called the Deutsch Halbblut. But the program never really got off the ground, and no dogs from it entered established Weimaraner lines.

Several years later, a member of the German Weimaraner club bred one of his Weimaraners to a well-known Pointer bitch. He then bred the offspring to each other. All this was done without the knowledge or permission of the club. When word finally reached the board of directors, they decided, reluctantly, to allow the program to continue under the guise of research into the phenomenon of hybrid vigor. If the offspring were capable of passing all the required tests, then further steps would be taken to blend the crossbred dogs into established Weimaraner lines. In the end, the experiment was declared a failure. The Pointer bitch threw pups with extremely bad bites. That was enough justification for the breed warden to terminate the program. When I asked club members in Germany about those years, one of them said, “That is a chapter in the history of the Weimaraner that is now closed, thank goodness!”

Elsewhere, rumors of crossbreeding continue to make the rounds. In the US, claims and denials of crosses to Pointers and GSPs have been around for years. In France, knowing winks are exchanged in some circles. The French are rumored to have crossed everything from Pointers to GSPs to Salukis into some lines. However, nothing in either country has ever been proven

or publicly declared. What we do know is that in both the US and in France there are still very few Weimaraners capable of winning all-breed field trials. If crosses have been made, they have not had

a huge effect overall. Perhaps they were done so long ago that they don’t really matter anymore, or they were not done widely or often enough to change the breed to the same degree as the GSP or Vizsla have been changed.

Clubs

Tests and Trials

The Weimaraner club of Germany follows a testing and breeding program similar to other JGHV-affiliated clubs. It sanctions VJP, HZP and VGP events, as well as various tracking tests. In Germany, Weimaraners must pass at least the first two levels of tests (VJP, HZP), as well as a coat, conformation and character examination, in order to be certified for breeding. The Austrian and the Czech clubs run similar tests, although they use a slightly different scoring system.

In the US, there is a fairly active AKC field trial scene for the breed. The Weimaraner Club of America and its affiliates organize 20 to

30 trials every year, including a

National Championship held near Ardmore, Oklahoma. Several kennels have been very successful in the field trial arena, and have done an outstanding job of keeping the hunt in their lines, while working toward developing class bird dogs for all-breed competition. The WCA also holds field-oriented ratings tests. Dogs can earn titles for upland bird work and/or retrieving. There is a small but growing number of Weimaraners participating in the NAVHDA testing system, with several kennels now using it to select their breeding stock (see a video of some of them

here, starting at about 12:50 mark).

In the UK, France, Italy, Holland, Denmark, Sweden, Norway and Finland, Weimaraners can occasionally be seen in field trials and hunt tests. Like their American counterparts, European Weimaraner enthusiasts outside of Germany, Austria and the Czech Republic tend to place more emphasis on the breed’s upland bird hunting abilities than on big game hunting or blood trailing.

Health: In addition to the health issues faced by other breeds, the Weimaraner seems to be at a somewhat higher risk for autoimmune reactions to certain vaccination protocols. As a precautionary measure, the Weimaraner Club of America

recommends that Weimaraner pups receive parvo and distemper shots separately, about two weeks apart. Weimaraners are also reported to be at a higher than average risk for a severe form of hypertrophic osteodystrophy (HOD), an inflammatory condition of the bones and other organs that can be fatal. Other issues of concern are bloat (gastric torsion) and von Willebrand’s disease.

FORM

The unique look of the Weimaraner is a double-edged sword. Having a hunting dog with a unique color and chiseled good looks is great. I've had Weimaraners for over 12 years, and I am still flattered when my hunting buddies tell me my dogs are handsome. But, on the other hand, the look of the breed has captured the attention of huge numbers of non-hunters who now make up the largest market for it. As a result, many breeders select almost exclusively for looks, and ignore the most important feature of the breed: its hunting instincts.

Size: Weimaraners can be substantial dogs, among the biggest of the Continental breeds. North American field-bred Weimaraners tend to be smaller than their show-bred compatriots.

Males: 59 – 70 cm

Females: 57 – 65 cm

Coat: Most Weimaraners have a short silver-grey coat and cropped tail. Long-haired Weimaraners are identical to the short-haired variety except for having a long, soft topcoat, with or without an undercoat. The long hair lies flat and measures 3 to 5 cm in length. It is somewhat longer on the ears and backs of the legs, and slightly shorter on the head. The tail develops a “plume” of long hair when the dog nears maturity. The tail of the long-haired Weimaraner is usually not cropped.

Long-haired Weimaraners were known to exist for many years before they were officially accepted in 1935, but have always been less common than the short-haired variety. Even today they only represent about 30% of the breed’s population in Germany and Austria; less in other countries. Curiously, the Weimaraner Club of America is the only Weimaraner club in the world to list the long-haired coat as a disqualifying fault. But the disqualification only applies to the show ring, so long-haired Weimaraners may participate in any other event open to pointing dogs.

Another type of coat known as

stockhaar is quite rare, and only occurs in dogs that carry both the short-hair and long-hair genes. It is a double coat with a medium-length, flat-lying topcoat, and thick undercoat with a slight amount of feathering sometimes seen on the backs of the legs. Mating a short-haired Weimaraner to a long-haired Weimaraner may produce a stockhaar coat, but it is not a sure bet. The same holds true for two short-haired Weimaraners that carry the recessive long-hair gene. There is only a slight chance that they could produce a stockhaar coat.

Color

The breed’s silver-grey color has always been its most distinctive feature. But a grey coat is not unique to Weimaraners. Pups with grey coats have cropped up from time to time in other breeds. Writing in

Weimaraner Heute, Dr. Werner Petri describes seeing grey pups in a litter produced by two black Middle Pinschers, and that prior to the Second World War, grey pups appeared in several litters out of solid brown German Longhaired Pointers. I’ve been told by breeders of GSPs in the Czech Republic and Slovakia that grey pups occasionally occur in their breed and are suspected of being throwbacks to a time when Weimaraners were crossed into GSP lines. A former president of the Cesky Fousek Club, Dr. Jaromir Dostal, has also confirmed that grey pups can also occur in Cesky Fousek litters.

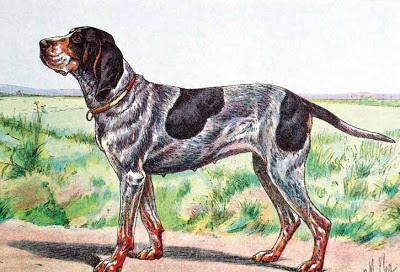

What is unique to the Weimaraner, at least among the pointing breeds, is that breeders specifically select for the silver-grey coat color. According to the breed standard, it is silver, deer or mouse grey, as well as shades of these colors. Genetically, silver-grey is actually a shade of brown that has been altered by a recessive dilution gene. If a Weimaraner is bred to a dog of another breed with a non-diluted coat color, the resulting pups are never grey. They are usually liver or black.

While silver-grey is the only officially recognized color of the Weimaraner, another coat color can occur. The so-called

blue Weimaraner has a distinctly blue-grey coat color similar to that of blue Great Danes, Dobermans or Italian Greyhounds. The color is actually a dilution of black. Blue Weimaraners have black noses and lips, and may have black mottling on the skin inside the mouth. Physically, other than the coat, blues look just like the silver-greys. They have a small but devoted following in the US, and have recently gained some ground in the UK, France and even in Germany, where breeders not affiliated with the parent breed club are now trying to cash in on the “rare” variety.

Unfortunately, blue fanciers are like the grey fanciers—most of them do not hunt! Blues are bred, almost exclusively, as companion animals. Since a blue coat is listed as a disqualification in the show ring, they are not even bred for blue ribbons. Of course, that is not to say that there aren’t any good blues out there; there certainly are. I am aware of several breeders of blues that test their dogs with NAVHDA and have earned respectable scores. Nevertheless, for hunters and field trial enthusiasts, finding a first-rate hunting dog among the blue Weimaraner population usually presents an even greater challenge than finding one among the silver-greys.

“Blues” remain a hot-button issue in Weimaraner circles but space does not permit an analysis of the issues involved. However, a resolution may be on the horizon. In 2009,

a club was formed in the US with the goal of establishing the Blue as a separate and independent breed. If you want to read my take on the Blue issue, here is a

link to a mini rant I wrote a while back.

UPDATE: I recently wrote about another coat type/color in Weims:

White.

FUNCTION

Field Search: I have seen Weimaraners that were ultra- close workers, hunting at a fairly methodical pace. I have also seen one or two that ran for the horizon like bats out of hell. However, most Weimaraners have a close to medium range and hunt at a medium gallop.

Judy Balog, a leading American Weimaraner breeder, says:

Good Weims can search a field as well as any other versatile breed. But even the widest-ranging Weimaraners are not run-offs. They keep a sharp eye on their owners and willingly hunt for the gun while handling kindly.

Pointing

The pointing instinct can be slow to develop in some Weimaraners. Once they mature, however, they are generally strong pointers. Those selected for field trials in the US and Europe tend to have a very strong pointing instinct that develops earlier. Americans, in particular, place more emphasis on style of point, and look for dogs that display a higher head and tail. Like most other Continental breeds, natural backing is occasionally seen, but it is not particularly common.

Retrieving

Most Weimaraners are natural-born re- trievers that show a strong desire to fetch anything and everything at a very early age. The retrieving instinct may, in fact, be one of the most deeply seated traits of the breed. Even in lines where the run and point have almost been completely bred out, the desire to retrieve often remains quite strong.

Tracking

Perhaps because of its Leithund heritage, the Weimaraner has always been known for a “deep nose”. In Germany, a lot of emphasis is placed on selecting and testing for tracking ability. A lower head is greatly valued. So is giving voice on track, a behavior called spurlaut. In America, many breeders prefer a higher head, but do not ignore tracking ability completely as it is an important aspect of upland game hunting and NAVHDA testing. However, there is very little emphasis placed on big game tracking among Weimaraner fanciers outside of Germany and Eastern Europe. Nor is there any attempt to select for traits such as spurlaut.

Water Work

Weimaraners can be excellent water workers. Some may need more encouragement than others when first being introduced to water, but once they have learned to swim, they can be top-notch performers. The short-haired version of the breed may not be the best choice for the late-season waterfowler. Even the long-haired variety, which is better able to work in cooler temperatures, may not be well suited to breaking ice in deep waters.

Judy Balog says that: The young Weim may need a little more early encouragement, but once they mature I think they’re hard to beat and most make top-notch water retrievers.

CHARACTER

With such a huge population and so many different lines of Weimaraners out there, it is difficult to describe a “typical” weimaraner. There is a wide range of personalities in the breed, running the gamut from eager-to-please gundogs to hyperactive basket cases. But if we limit the discussion to dogs with a well-balanced character we can say that, in general, Weimaraners are friendly, extremely intelligent, high-energy dogs. They are not well suited to living in a kennel, and not really the kind of dog that can be left to their own devices around the house. They are often slow to mature, both physically and mentally.

Training

The breed is particularly well known for forming a very strong attachment to its owner/handler. This can be a double-edged sword when it comes to training. The fierce loyalty and tremendous desire to please are great assets but, if not handled properly, they can sometimes lead to dogs that show very little independence. Again, it really depends on what lines they come from and how they are raised. Generally speaking, training a Weimaraner from good, proven stock is fairly straightforward.

Protection

For over a century, Weimaraner breeders in Germany have sought to breed courageous dogs with a strong protection instinct. Weimaraners are the only pointing breed in Germany required to pass tests designed to evaluate these traits.

Tanja Breu-Knaup, a leading breeder of long- haired Weimaraners in Germany, explains that the breed’s reputation of being

mannscharf (literally “man-sharp”) is slowly fading.

In the 1980s, when I first showed up to a training session with my dogs, everyone thought that they would be aggressive. But I proved to them that my dogs are NOT aggressive. Thankfully, things have changed since then.

Instrumental in the public’s change in attitude has been the decision by the parent club to modify the testing procedure.

Steve Graham, an American who has imported Weimaraners from Germany, explains:

The man-sharpness test (Mannscharfprüfung) was replaced by the new Wesenstest in 2001. In the older test, the handler holds the dog on a lead, and the judge, armed with a stick, makes threatening moves toward the handler. The dog is expected to show courage and willingness to defend its handler.In the newer test, the dog must also prove that it is not fearful or aggressive. A group of a about a dozen people forms a large circle around the handler and dog. Slowly, the people move toward the center. When the circle is more or less closed, the handler must let go of the leash and exit the circle leaving the dog behind. Once outside of the circle, the handler calls the dog. The dog should then go to the handler. When this is done, the handler and dog re-enter the circle. Judges look for any hint of fear or aggression. If they detect the slightest amount of either, the dog is prohibited from breeding.

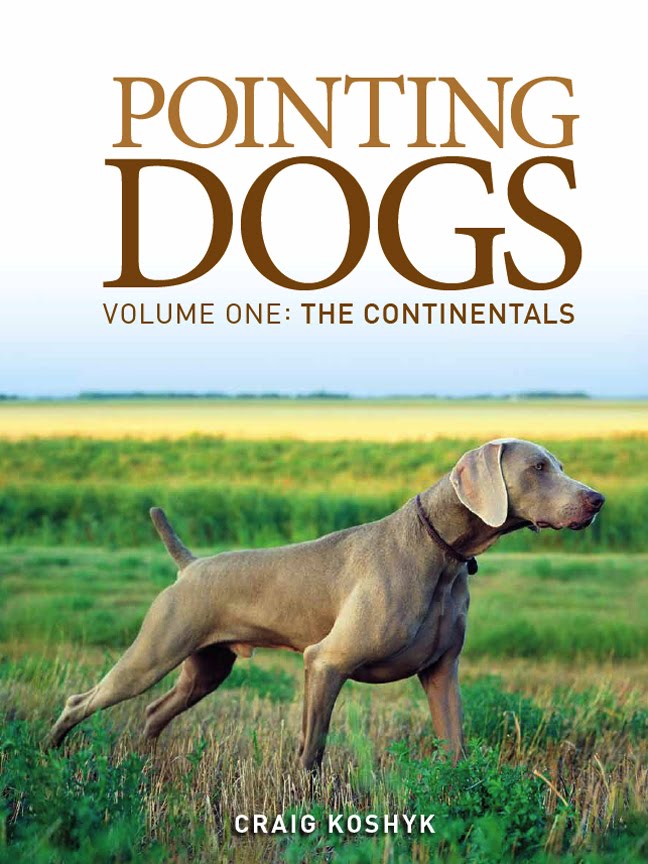

Read more about the breed, and all the other pointing breeds from Continental Europe, in my book Pointing Dogs, Volume One: The Continentals