A good friend of mine was born and raised in New Zealand.

He moved to Canada more than two decades ago to pursue his life’s passion—falconry. He had flown his birds of prey over Springer Spaniels and German Shorthaired Pointers in his homeland, but when he moved to Manitoba he decided to go with another breed. He wanted a sturdy pointing dog able to handle the tough cover and harsh climate of central Canada. After weighing the pros and cons of several breeds, he chose the German Wirehaired Pointer.

He acquired two males and hunted with them for several years. Then he decided to add a female to his kennel. I was there when she arrived by plane from Germany. Despite having spent over 14 hours in a crate, the minute that pup was let out she jumped into her new owner’s arms, licked his cheek and then ran to a small pond on the other side of the yard. When she got there, without any hesitation, she dove in and gave chase to a family of ducks.

She was just four months old.

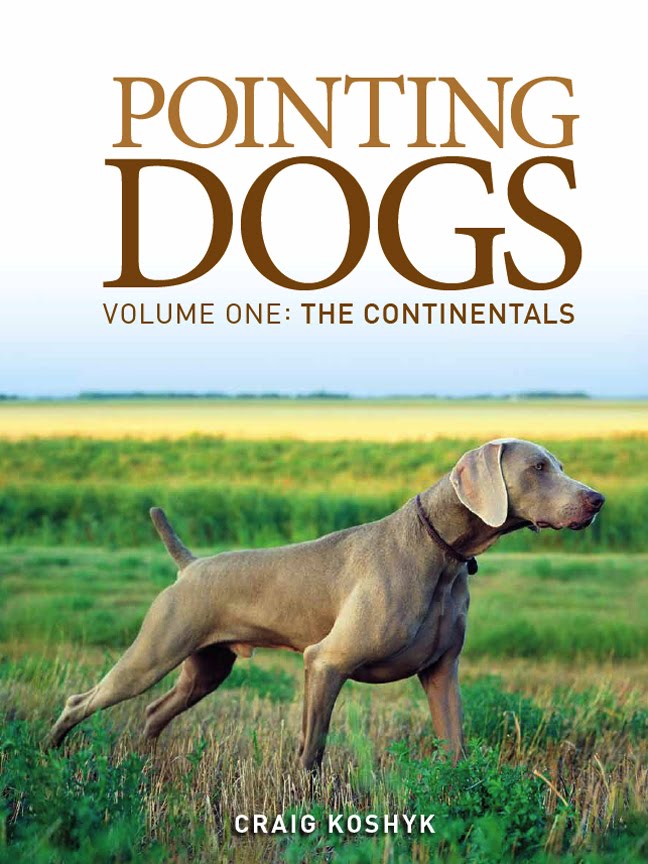

That young pup eventually grew up to be an absolutely superb gundog. That’s her in the photo above. To me, she will always represent the very essence of the German Wirehaired Pointer: a rough and tumble, intensely loyal, hard-working gundog. And the fact that a falconer from New Zealand living in Canada could get a pup from a breeder in Germany and have it start hunting the minute its feet hit the ground is testament to the incredible achievements of a small group of people who had the courage to follow a revolutionary idea nearly a century ago.

The story of the German Wirehaired Pointer begins around the turn of the 20th century as the early experimental period of dog breeding was coming to an end. By then, many breeds had been declared separate and distinct and their stud books closed to so-called foreign blood. Kennel clubs, registries and breeding associations were forming across Europe and breeders were lining up to earn blue ribbons in the show ring for “improving” their breed.

Increasingly, the trend among many breeders was to base their selection of breeding stock on two main criteria: appearance and pedigree. They believed that selecting the best looking animals and maintaining them within a closed registry was the most appropriate way to improve their dogs. But hunters soon discovered the fatal flaw in this way of thinking. They realized that selecting dogs based on appearance alone was futile. Unless a strict testing program was established to select dogs based on their inherited hunting abilities, there would be no way to make any progress. However, most breeders stopped short of actually challenging the closed stud book and the concept of pure breeding. They still believed that breeds should be kept separate and breeders should avoid “contaminating” their lines with outside blood.

The creators of the German Wirehaired Pointer held a different view. They believed that all rough-haired pointing breeds were members of the same family and that breeding among them should be allowed. They also believed they should be able to cross to an unrelated breed, the Deutsch Kurzhaar (German Shorthaired Pointer). Naturally, many members of the hunting dog establishment considered this attitude an affront to the sanctity of pure breeding. Yet, despite considerable risk to their reputations and fierce condemnation by their peers, supporters of the German Wirehaired Pointer stuck to their convictions.

Like other breeders of the time, they knew that the only way to breed better hunting dogs was to select breeding stock based on the dogs’ abilities, not their outward appearance. This is the essence of the famous saying

“durch Leistung zum Typ”, which means “form follows function”. But unlike the others, these early visionaries went even further. They believed that everything follows function, even the most sacred tenant of them all: breed purity.

They argued that dividing the varieties of rough-haired dogs into supposedly pure, independent breeds was just “hair splitting”. They could see that it was leading to the splintering of forces at a time when everyone should be working together. So they decided to join forces and even came up with slogans to summarize their approach. They urged each other to “take the good where you find it” and to “breed as you like but be honest about it and let the results be your guide”. Even today, such ideas can cause a stir. But back then they must have seemed like heresy to members of the canine establishment.

In an effort to gain some insight into what it must have been like at the time, I asked a friend in Germany, Wilhelm Heinrich, a GWP owner with a keen interest in the history of the breed, to translate portions of club newsletters published by the Verein Deutsch Drahthaar and to offer me his thoughts

on the early years of the breed.

"When the VDD was founded, most of the members were renegades from the Pudelpointer club that was founded in 1897. The most important of them was Alexander Lauffs, the VDD president from 1902 to 1934. He was obviously an impressive personality and very influential in many aspects, particularly in the selection of his comrades-in-arms for his cause. Another important founding member, Mr. Berkhan, was also a Pudelpointer renegade. In 1927, when looking back on the wild days of breeding around 1900 and on the battles since then, he wrote in the Drahthaar club newsletter No.5, May, 1927:

I was still convinced that for breeding Pudelpointers I would

need one Pointer and one Poodle. I finally succeeded in acquiring a splendid pair of Poodles. Even the renowned cynologist,

Dr. Steffens-Lollar, agreed, upon presenting him my Poodle, Rappo, in the hunting field, that one would hardly find a better Poodle for breeding. Rappo was bred to some beautiful and talented purebred Pointer bitches. The offspring were, of course, not half bad, but not quite phenomenal. According to Oberländer and Hegewald, this crossing should have been superior to everything else bred at that time. So, was the conclusion, that for a good versatile dog the mixture of Poodle and Pointer alone was insufficient, not a natural one, and that a third blood, namely that of the Deutsch Kurzhaar [GSP] would be useful, if not essential for that purpose? I first spoke out about this opinion in [the sporting magazine] Hundezucht und Sport. I received countless approvals, eminent breeders such as Hass-Birkbusch and Lauffs-Unkel agreed, and from this idea the VDD was soon founded.”

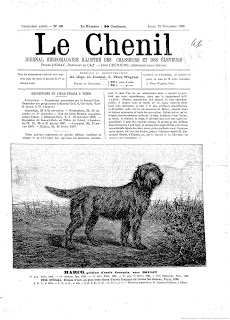

To the left is the front cover of Le Chenil for the week of Nov. 18, 1886. It features an illustration of Marco the most famous of Boulet's dogs. The caption beneath the photo reads: Marco, French pointing griffon of the Boulet breed. 1st Prize, Paris 1882 with special mention, 1st Prize, Spa 1882, 1st Prize, Le Havre 1882, Prize of Honor, Paris 1886, Special Prize, Le Bronze d'Art for the handsomest French pointing dog of all classes, Paris 1886 (then Marco's registration numbers are given for various studbooks) Breeder and owner, M. Emmanuel Boulet from Elbeouf.

To the left is the front cover of Le Chenil for the week of Nov. 18, 1886. It features an illustration of Marco the most famous of Boulet's dogs. The caption beneath the photo reads: Marco, French pointing griffon of the Boulet breed. 1st Prize, Paris 1882 with special mention, 1st Prize, Spa 1882, 1st Prize, Le Havre 1882, Prize of Honor, Paris 1886, Special Prize, Le Bronze d'Art for the handsomest French pointing dog of all classes, Paris 1886 (then Marco's registration numbers are given for various studbooks) Breeder and owner, M. Emmanuel Boulet from Elbeouf.