Less is More.

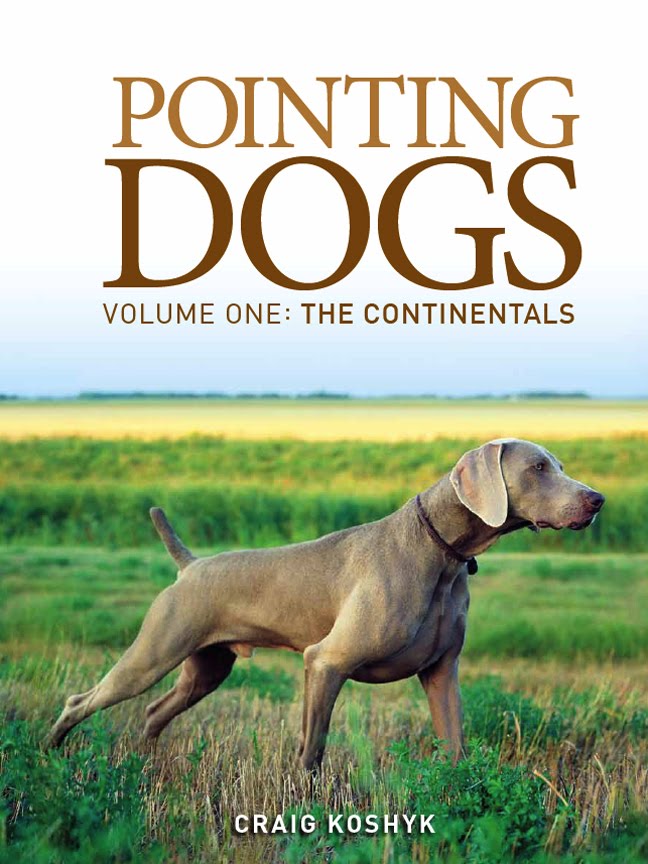

Craig Koshyk

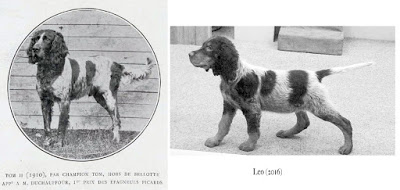

UPDATE: Leo earned a perfect score of 112/112!

This weekend I will be running my new pup Léo in a NAVHDA Natural Ability test hosted by the Red River Chapter near Fargo. Born last December, he will be too old to run next summer – the age limit is 16 months – so I am running him at 8 months of age before he's ever really hunted and without any formal training by me. But that's OK, in keeping with his French heritage, I'm following the take it easy and 'less is more' philosophy of bringing a bird dog along. So on test day, my goal is to just have fun, cross my fingers and hope for the best.

For those unfamiliar with the test, here is what's involved. (From the NAVHDA website, with my notes added):

The Natural Ability Test is organized into four main segments:

A few minutes into the run, a gunner further back fires a blank from a shotgun, twice. The judges want to see if the shot affects the dog in a negative way. So far Leo has shown no reaction to gunfire other than to look over towards the sound, if that. So I think he will be fine in that regard, but it will be interesting to see how he reacts to 'hunting' in a field with a half dozen people around. I've only ever run him by myself, but I'm pretty sure he will just ignore the others and have fun searching for game.

Prior to each dog's turn pen-raised birds, usually Chukar partridge, are placed in the field. If all goes well, the dog finds some birds and points them. Unlike the higher levels of NAVHDA testing, in NA tests, the dog does not have to wait until the handler flushes the bird. As long as it points for a few seconds, it should get a decent pointing score.

Léo seems to have a strong natural point. I've seen him point rabbits in the city and the occasional song bird in the field. I worked him on planted pigeons a couple of times and he pointed them well. He has even shown a tendency to back (honour) other dogs on point. But Léo hasn't been exposed to game birds yet. We avoided wild birds over the summer since they were nesting or had young chicks and I don't have access to pen-raised Chukars. So when we hit the field in the NA test, I will just cross my fingers and hope that Léo's instincts kick in when he comes across birds.

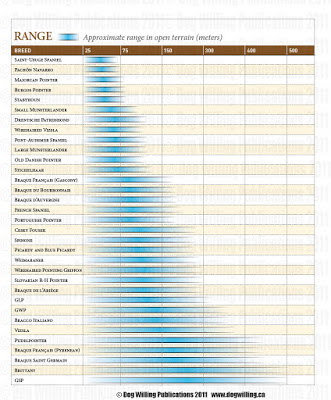

Another thing judges look for during this phase is how well the dog hunts with and for the handler. They want to see a certain amount of independence from the dog, but don't want it to take off for the horizon. Then again, they don't really want to see the dog amble about mere meters from the handler either. Ideally, the dog will hunt at a suitable range for hunting according to the the conditions of the day; not too far, not too close. It should also show a decent amount of drive and respond to commands (if any) given by the handler.

When I take Léo out to the fields around here, he runs at a medium to fast gallop, holds his head just above the shoulder line, and makes casts out to about 75 yard. But, as mentioned, he hasn't really been on game birds before. So I wouldn't be surprised if he opens up even more once he realizes that there are birds in the field. He may even fall slightly deaf to my whistle or commands. So my plan is to just keep my yapper shut and hope that he doesn't disappear over the horizon on a bird-fueled bender.

In theory, this should be a relatively easy job for a well-bred gundog. The bird should leave a decent scent trail behind it and the dog should be able to follow it fairly well. But there are tons of variables involved, from the humidity (or lack thereof) of the air and grass, to the length of the cover, to how far and fast the bird went, so no matter how much prep you do for this phase, or how well your dog did in any practice tracks you've done, it is always a complete crap shoot on test day.

I've done exactly zero prep for this phase with Léo. I might get one practice track in this weekend if I can find a pheasant, but in all likelihood, the track at the test will be Léo's first. And I don't really know how it will go. Léo loves to run and he runs with a high head. So he may follow the trail for a bit, but then decide that it's best to just go into field search mode instead of track mode. Or he may track it perfectly well. I've seen him follow a rabbit track for over 100 yards, so I know he has some tracking instincts. In any case, just as in the field search portion, I will cross my fingers and hope for the best.

4) Judgment of Physical Characteristics.

1) Field Phase - Each dog is hunted for a minimum of 20 minutes and is evaluated on:

- Use of Nose

- Search

- Pointing

- Desire

- Cooperation

- Gun Shyness

A few minutes into the run, a gunner further back fires a blank from a shotgun, twice. The judges want to see if the shot affects the dog in a negative way. So far Leo has shown no reaction to gunfire other than to look over towards the sound, if that. So I think he will be fine in that regard, but it will be interesting to see how he reacts to 'hunting' in a field with a half dozen people around. I've only ever run him by myself, but I'm pretty sure he will just ignore the others and have fun searching for game.

Prior to each dog's turn pen-raised birds, usually Chukar partridge, are placed in the field. If all goes well, the dog finds some birds and points them. Unlike the higher levels of NAVHDA testing, in NA tests, the dog does not have to wait until the handler flushes the bird. As long as it points for a few seconds, it should get a decent pointing score.

Léo seems to have a strong natural point. I've seen him point rabbits in the city and the occasional song bird in the field. I worked him on planted pigeons a couple of times and he pointed them well. He has even shown a tendency to back (honour) other dogs on point. But Léo hasn't been exposed to game birds yet. We avoided wild birds over the summer since they were nesting or had young chicks and I don't have access to pen-raised Chukars. So when we hit the field in the NA test, I will just cross my fingers and hope that Léo's instincts kick in when he comes across birds.

Another thing judges look for during this phase is how well the dog hunts with and for the handler. They want to see a certain amount of independence from the dog, but don't want it to take off for the horizon. Then again, they don't really want to see the dog amble about mere meters from the handler either. Ideally, the dog will hunt at a suitable range for hunting according to the the conditions of the day; not too far, not too close. It should also show a decent amount of drive and respond to commands (if any) given by the handler.

When I take Léo out to the fields around here, he runs at a medium to fast gallop, holds his head just above the shoulder line, and makes casts out to about 75 yard. But, as mentioned, he hasn't really been on game birds before. So I wouldn't be surprised if he opens up even more once he realizes that there are birds in the field. He may even fall slightly deaf to my whistle or commands. So my plan is to just keep my yapper shut and hope that he doesn't disappear over the horizon on a bird-fueled bender.

2) Tracking Phase - The dog is given an opportunity to track a flightless running pheasant or chukar.

During

this phase, one pheasant for each dog is placed in a field and coaxed

into running downwind for about 50 yards. The dog is then brought to

where the bird was first released so that it can (hopefully) follow the

track to the bird. If the dog does follow the track and manages to find

the bird, it can point it or fetch it up. It doesn't really matter. It

doesn't really have to find the bird to get a good score. What the

judges want to evaluate is how well the dog can actually follow a track.

In theory, this should be a relatively easy job for a well-bred gundog. The bird should leave a decent scent trail behind it and the dog should be able to follow it fairly well. But there are tons of variables involved, from the humidity (or lack thereof) of the air and grass, to the length of the cover, to how far and fast the bird went, so no matter how much prep you do for this phase, or how well your dog did in any practice tracks you've done, it is always a complete crap shoot on test day.

I've done exactly zero prep for this phase with Léo. I might get one practice track in this weekend if I can find a pheasant, but in all likelihood, the track at the test will be Léo's first. And I don't really know how it will go. Léo loves to run and he runs with a high head. So he may follow the trail for a bit, but then decide that it's best to just go into field search mode instead of track mode. Or he may track it perfectly well. I've seen him follow a rabbit track for over 100 yards, so I know he has some tracking instincts. In any case, just as in the field search portion, I will cross my fingers and hope for the best.

3) Water Phase - The dog is tested for its willingness to swim.

The only problem I have with Léo and water is getting him OUT of it! So I am pretty sure he will do well in this portion of the test.

The only problem I have with Léo and water is getting him OUT of it! So I am pretty sure he will do well in this portion of the test.

4) Judgment of Physical Characteristics.

The following are judged throughout the Natural Ability Test:

- Use of Nose

- Desire to Work

- Cooperation

- Physical Attributes

No game is shot, and no retrieves are required during the Natural Ability Test.

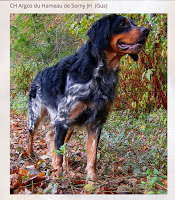

From what I can tell, Léo has very good nose and his desire for work and cooperation are excellent. He really is an outstanding pup in every way. He's super easy to live with, friendly, loves to hunt and cuddle, and is pretty darn handsome as well. We are really pleased with him and look forward to many hunting seasons with him.

But for now, I need to pack my bags and then do some stretches for my fingers...they will be crossed all weekend!

From what I can tell, Léo has very good nose and his desire for work and cooperation are excellent. He really is an outstanding pup in every way. He's super easy to live with, friendly, loves to hunt and cuddle, and is pretty darn handsome as well. We are really pleased with him and look forward to many hunting seasons with him.

But for now, I need to pack my bags and then do some stretches for my fingers...they will be crossed all weekend!