On Range

Craig Koshyk

Hunting dogs are generally categorized according to the job they are expected to do and the manner in which they should do it. Thus the retrieving breeds; Labradors, Chesapeakes, Golden, Flat and Curly Coats, are used to do what their name would imply. They retrieve shot game to the hunter. While there may be some debate about the finer points of the expected performance, there is no disagreement about the basic task: the dog must leave the hunter, make its way to the downed game, pick it up and bring it back.

The flushing spaniels, Springers, Cockers, Clumbers, Sussex, Welsh and Field are selected, bred and trained to search for game and force it to flight within gun range of the hunter. They are expected to retrieve downed game as well. Here again there may be some disagreement regarding the exact manner in which the dog should work, but the basics are not in dispute. The dog must seek and flush game within range of the gun and retrieve what is shot.

Pointing breeds however, do not enjoy such a consensus of opinion when it comes to how they should do their job. Other than agreeing that the dog should find and point game, everything else, from searching to retrieving, to tracking, to pace, and gate, even to the posture the dog assumes while pointing can be, and usually is, the subject of heated debate among pointing dog enthusiasts.

This is one of the principle reasons that there are so many more breeds of pointing dogs than there are retrievers or flushing spaniels. Different pointing breeds have been developed to perform similar tasks but in sometimes very different ways. Furthermore, many breeds can now be subdivided into different strains with field performance characteristics so dissimilar that they can almost be considered different breeds altogether.

The one area that stands above all others as a source of endless debate, especially in America, is the question of range. Since a pointing dog’s main purpose in the field is to find game, point it and, hopefully, hold the game there until the hunter arrives, it can work at distances beyond the range of a shotgun. So the question then becomes, how far is too far?

Traditionally, all of the Continental breeds were selected and trained to hunt only slightly further out than flushing dogs, about 50 or 60 meters at the most. Nowadays, a few breeds are still supposed to have that sort of range, but most are expected to run somewhat wider than that, at least some of the time. What’s more, over the last 50 years, bigger and faster running strains within most breeds have been developed. In fact, in some breeds, there are now lines of dogs that approach the speed and range of English Pointers and English Setters.

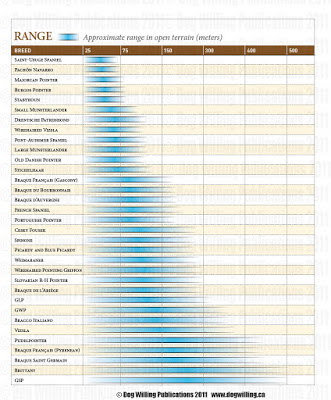

Be that as it may, I have come up with a chart that illustrates the typical range for each of the Continental pointing breeds, but we need to keep the following things in mind when consulting it.

THE BEST RANGE IS THE ONE THAT SUITS YOU: One of the most common sources of frustration among pointing dog owners is a mismatch between the range the hunter would like his dog to run at, and the range the dog’s genes tell it to run at. Most experts agree that a pointing dog’s range is largely an inherited trait. There are methods that can be employed to modify this range making a wide-ranging dog work closer or, more difficultly, making a close-working dog range further out—but in general the distance from the handler at which the dog is most comfortable hunting is mainly determined by its genes. So, finding a breed that has the kind of range you are comfortable with, and is suitable for the game and terrain you hunt, is very important.

THESE ARE BALLPARK FIGURES: The chart is not based on anything close to a scientific survey. Some of the distances given are based on the preferred ranges stated in the breed’s published work standard, but most are based on nothing more than the breed’s reputation or the generally accepted norm as expressed to me by the breeders and owners I have spoken to.

THERE ARE EXCEPTIONS: There are outliers in every breed. Some may run way bigger than the average, and others may work closer in. In many breeds, this applies to various strains and lines that may show significant differences in range. That is why the chart shows a wider spectrum of ranges for some breeds.

“HORSES FOR COURSES”: Generally speaking, within any given breed, breeders who select their stock for field trials tend to produce dogs that are toward the bigger running end of the spectrum. Other breeders may seek to produce closer-working dogs suitable for different types of terrain or game.

TO THE FRONT OR SIDE TO SIDE: In some countries, dogs are expected to run in a windshield wiper pattern in front of the hunter. In that case, the distances given would indicate how far the dog usually ranges out to one side or the other. In other countries, dogs are encouraged to “seek objectives”. They should run to areas of cover that are likely to hold birds no matter where they may be, to the left, to the right, or out in front.

DOGS ADJUST THEIR RANGE: The distances given reflect the usual range for the breed when hunting in open fields. Most dogs will adjust their range when working in tighter cover. The same dog that ranges out to over 300 meters across a stubble field for grey partridges might not go beyond 40 or 50 meters in the alder thickets in pursuit of woodcock. And yes, as mentioned above, a dog’s range can be adjusted. But it is easier to teach a wide-running dog to stay closer than it is to make a close working dog work further out

Enjoy my blog posts? Check out my book Pointing Dogs, Volume One: The Continentals