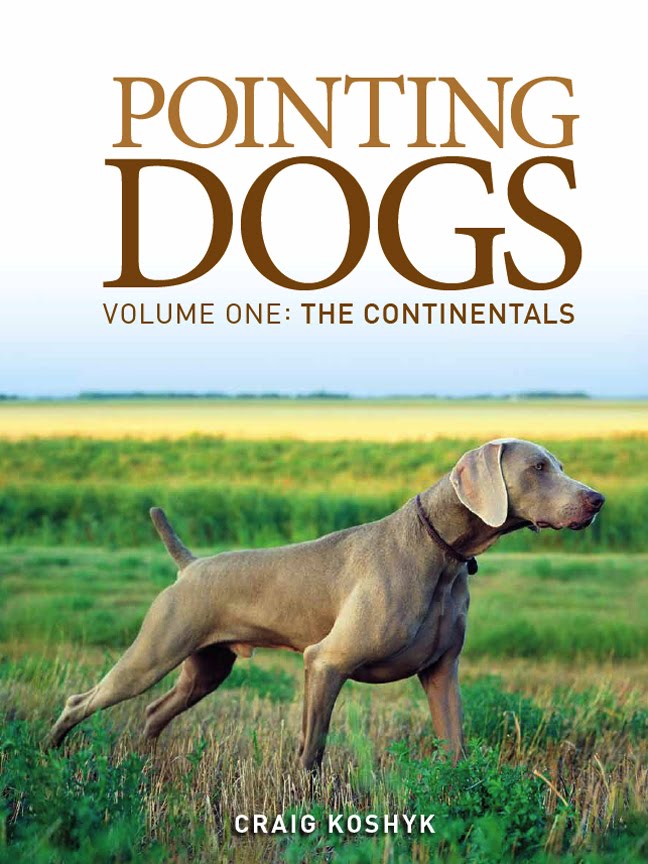

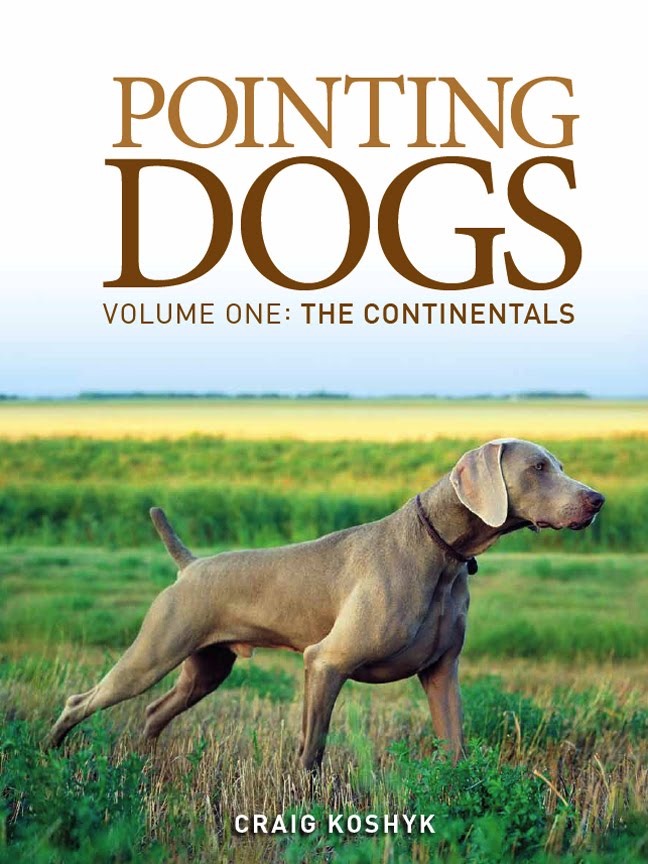

A Whitemaraner?

Craig Koshyk

I came across a very interesting photo today. It is of a really cool looking dog with a mainly white coat and a grey …as in Weimaraner grey… head. It also has a grey spot on its back near the tail.

I have seen Weims with a white "blaze" or spot on the chest and even one that had a couple of white toes, but this dog had far more white than grey in its coat. I shared the photo on Facebook and remarked how cool it would be to hunt over him since he would be really easy to see and not blend into the forest like my all-grey dogs do.

I had no idea that this would be the start of a somewhat contentious debate (I was even 'de-friended' by one person who thought I was on a mission to destroy the purity of the breed!). In the comment section of the photo more than one person stated that the dog could not be a "pure" Weimaraner (others were less than polite, calling the dog a "mutt" and dropping F bombs.) And a few people wrote that the dog must be the result of a cross with a GSP or with a Pointer. And they may be correct. After all there is no genetic law that makes it impossible for dogs of different breeds to mate. All they need are testicles and ovaries.

But there are a couple of things that make me wonder if the dog might actually be as pure as any other all-grey Weim. First of all, the owner has stated that it is from two pure grey Weims. And apparently other similar dogs have had their DNA tested by Dr. Epplen at the University of Bochum and have been declared "100% pure". I've heard from other folks that they have also seen this type of coat in litters of pure-bred all-grey Weims in the US. Here is a link to some photos and a discussion thread about one such dog.

The other thing that got me thinking was not really the white in the coat, but the grey. You see, the Weim coat is basically a brown (liver) colour that is "watered down" by a dilution factor that messes with the melanin in the hair shafts. The mechanism is a bit complicated but my friend Sheila Schmutz explains it very well here. What is important to remember is that the dilution factor is recessive. That means both parents must have the factor in order for their pups to express it. So if the Weims in the photos are in fact the results of cross breedings to GSPs or Pointers as has been suggested, then the Pointer or GSP parent must have had the dilution factor too.

Years ago, I actually saw some pups from a Weimaraner x Vizsla "oops" breeding. But they were all solid liver. None of them had any hint of grey... and that make sense. Only one parent (the Weim) would have had the dilution factor. The other (the Vizsla) did not have the dilution factor so the pups could never be grey.

Finally, there is the possibility of some kind of developmental problem occurring during the pup's gestation. Apparently, while pups are still in the womb, the migration of the pigments (melanocytes) that bring colour to the dog can sometimes be delayed or interrupted. Sheila Schmutz writes that:

Because melanocytes migrate down from the spinal column during embryogenesis not all animals complete this process by birth or thereafter. In dogs, it is therefore not uncommon to see white toes on an otherwise black or red dog. This is probably more a random event than the result of a specific allele. Another common "white spot" on dogs occurs on the chest. This must again be a site where melanocytoe migration occurs very late in fetal development and a cold or other developmental delay prevents the completion of melanocyte migration. It may be that the rate of melanocyte migration is itself inherited.

In some dogs… a white chest spot occurs. Some standards mention this as a fault. This is likely simply incomplete pigment migration in the particular individual, and not an inherited trait. Such small amounts of white on the chest or on the toes, do not seem to be caused by mutations… More here.

I have seen Weims with a white "blaze" or spot on the chest and even one that had a couple of white toes, but this dog had far more white than grey in its coat. I shared the photo on Facebook and remarked how cool it would be to hunt over him since he would be really easy to see and not blend into the forest like my all-grey dogs do.

I had no idea that this would be the start of a somewhat contentious debate (I was even 'de-friended' by one person who thought I was on a mission to destroy the purity of the breed!). In the comment section of the photo more than one person stated that the dog could not be a "pure" Weimaraner (others were less than polite, calling the dog a "mutt" and dropping F bombs.) And a few people wrote that the dog must be the result of a cross with a GSP or with a Pointer. And they may be correct. After all there is no genetic law that makes it impossible for dogs of different breeds to mate. All they need are testicles and ovaries.

But there are a couple of things that make me wonder if the dog might actually be as pure as any other all-grey Weim. First of all, the owner has stated that it is from two pure grey Weims. And apparently other similar dogs have had their DNA tested by Dr. Epplen at the University of Bochum and have been declared "100% pure". I've heard from other folks that they have also seen this type of coat in litters of pure-bred all-grey Weims in the US. Here is a link to some photos and a discussion thread about one such dog.

The other thing that got me thinking was not really the white in the coat, but the grey. You see, the Weim coat is basically a brown (liver) colour that is "watered down" by a dilution factor that messes with the melanin in the hair shafts. The mechanism is a bit complicated but my friend Sheila Schmutz explains it very well here. What is important to remember is that the dilution factor is recessive. That means both parents must have the factor in order for their pups to express it. So if the Weims in the photos are in fact the results of cross breedings to GSPs or Pointers as has been suggested, then the Pointer or GSP parent must have had the dilution factor too.

Years ago, I actually saw some pups from a Weimaraner x Vizsla "oops" breeding. But they were all solid liver. None of them had any hint of grey... and that make sense. Only one parent (the Weim) would have had the dilution factor. The other (the Vizsla) did not have the dilution factor so the pups could never be grey.

Finally, there is the possibility of some kind of developmental problem occurring during the pup's gestation. Apparently, while pups are still in the womb, the migration of the pigments (melanocytes) that bring colour to the dog can sometimes be delayed or interrupted. Sheila Schmutz writes that:

Because melanocytes migrate down from the spinal column during embryogenesis not all animals complete this process by birth or thereafter. In dogs, it is therefore not uncommon to see white toes on an otherwise black or red dog. This is probably more a random event than the result of a specific allele. Another common "white spot" on dogs occurs on the chest. This must again be a site where melanocytoe migration occurs very late in fetal development and a cold or other developmental delay prevents the completion of melanocyte migration. It may be that the rate of melanocyte migration is itself inherited.

In some dogs… a white chest spot occurs. Some standards mention this as a fault. This is likely simply incomplete pigment migration in the particular individual, and not an inherited trait. Such small amounts of white on the chest or on the toes, do not seem to be caused by mutations… More here.

In the most recent edition of the Weimaraner club of Germany's magazine Weimaraner Nachtrichten (Dec, 2011), there is an article written by Dr. Ilka Schalwat. The title of the article is White markings in the Weimaraner Coat are multifactorial and not purely hereditary. Here are a few quotes (please excuse my less than ideal translation, my German really sucks....)

As breeders, we bear great responsibility for the quality of our breed, the Weimaraner. Our goal should be to follow the what the breed standard specifies. But we should also strive to meet the overall objectives of the Weimaraner Club which are: breeding to improve Weimaraner as a hunting dog, fight disease and ensure good health.

Several years ago with these objectives in mind I chose a promising athletic males from my A-litter. He was recognized as a top male that has been very successful especially for hunting wild boar. The VGP tested male had a small white patch on his chest, to which I never attributed any importance since he met the FCI standard. But during the physical breeding examination I learned for the first time that the size of the spot on the breast is a factor for breeding considerations.

This experience was a surprise to me, and enough reason to make me concerned about the "inheritance" of white markings. The mother and the father of that dog were both without white markings, so I was quite astonished that the some puppies in my A-litter had white and some did not. At the recent dog show in 2011 I saw an entire litter from a well-known kennel, where all the litter mates had "too much"white.

For many it was incomprehensible. This really very dramatic experience guided my thoughts while I was planning my C-litter. I asked myself: How can I as the breeder reduce the risk for white markings in the selection of breeding partners? By what breeding methods can I use to limit the risk? I studied all

the stud books of the last 10 years and compared them with the litter registration. I quickly realized that the white markings were clearly not just an issue from 100 years ago when it was a typical Weimaraner phenomenon, but it was still an issue today.

Every year at least 25% of our puppies are noted to have white markings. In the last 10 years the rates have fluctuated, from 20 to 30%.... and I realized from the study of breeding books and notes that there is no indication for a possible mode of inheritance, no way to predict if a puppy will or will not have white markings.

I consulted with, Prof. Dr.Jörg Epplen at the Ruhr University in Bochum, the well-known Weimaraner supporter who has written numerous articles on inheritance in our club magazine. His reply surprised me.

"White spots are caused by many factors, not exactly hereditary, and certainly not by a single feature. They stem from delayed melanocyte migration "

Apparently, the formation of white spots is not yet fully elucidated. But leading scientists looking into the question believe the following: In the embryonic stage, melanocytes come from the neural crest (embryonic precursor structure to the spinal cord) then, along with the skin stem cells migrate. But a developmental delay due to infection or other problem, even if it is only for a few days during the pregnancy, can mean that the migration of melanocytes to the most remote places such as chest and paws do not make it in time.

Therefore, white markings may, in my opinion, be tolerated in the breed standard if the spot is not too large. And not all spots remain visible for a lifetime, because the pigmented hair can continue to proliferate as the dog matures. Excluding a dog from breeding because of a little white blaze is therefore unnecessary… such exclusion does not contribute to the improvement the race.

Even Dr. Werner Petri pointed out in his widely acclaimed textbook "Weimaraner Heute" suggests that not only at the beginning of Weimaraner breeding more than 100 years ago but even well into the last century, almost all Weimaraners had white markings (Petri Weimaraner Heute, 2003).

Due to increased breeding regulation in recent years, with regard to size and location of what are truly incidental white markings, an unfortunate negative selection pressure for breeding Weimaraners without white has emerged and some people want a "reinterpretation" of the standard.

But compared to hunting performance, health and good hips, white markings should only play a minor role. Everyone now wants to keep his kennel completely free of "white". And if you now have potential puppy buyers prevented from buying a puppy because of some white, it is a senseless waste of valuable genetic variability.

EDIT: It looks like a similar thing can happen to Deer too! (unless of course it is cross bred to a Pointer :)

I've received a surprising number of emails and comments regarding the mystery of the "Whitemaraner". In fact, my blog post has had nearly 500 visitors in less than 24 hours. So I thought I would make another post with some new information I have gathered. Read more here.