Dog breeds come and go. Some take centuries to develop and others are created almost overnight. Some slowly fade away and others disappear in the blink of an eye. For a very few breeds, there can even be a sort of resurrection. The Braque du Bourbonnais is one such breed. There are references to it as far back as the 16th century, but it had disappeared by the 1960s. Today, thanks to the efforts of a group of breeders led by a man of vision, it has returned.

HISTORY

A lot of breeds are said to be as old as the hills, but not many have any real proof of their ancient heritage. For the Braque du Bourbonnais, however, there is a fairly compelling document that does seem to prove that dogs matching its description have been around since at least the late 1500s. It is an illustration by the renowned Italian naturalist

Ulisse Aldrovandi that shows a dog with a striking resemblance to the modern Braque du Bourbonnais. It is titled

Canis sagax ad coturnices capiendas pantherinus, which means “keen scented panther-like (i.e., spotted) dog for catching quail”. In one of his manuscripts Aldrovandi also mentions a Canis Burbonensis (dog from Bourbonnais) Naturally, breed enthusiasts point to these references as proof that the Braque du Bourbonnais is one of the oldest breeds of short-haired pointing dogs. But they do concede that, like all short-haired pointing dogs, it ultimately traces back to the original stock from southern France and northern Spain. Adolphe de La Rue, wrote in

Les Chiens d’Arrêt Français et Anglais (1881):

As for the origins of the Bourbonnais dog, which is a short-tailed breed, there is no need to look anywhere else than at the large brown Braque; the first, most ancient of our breeds. Once this is admitted, it is no longer doubtful that families where individuals are always born with a short tail have in their veins the pure and precious blood of the primitive breed from which they descend.

Until the mid-1800s, the tail-less pointing dogs of the Bourbonnais region of France were more or less unknown in the rest of the country. But as the dog scene developed, the Braque Courte Queue (short-tailed braque) soon became a standard fixture at dog shows and gained a good number of converts among French hunters. But the breed’s good fortunes did not last very long. By the early 1900s, it was obvious that breeders had become fixated on its unique coat color and its naturally short tail. Alarmed by an increasing number of deaf, infertile or even albino individuals appearing in the breed, the great dog expert Pierre Mégnin warned of breeding too tightly among a very limited number of families. Fortunately, sensible breeders heeded his advice and began crossing to other breeds, principally English Pointers.

An extraordinary document survives from that era and offers insight into what the situation was like:

an article written by Mr. E. Dubut, a self-described

vieux fervent de notre brave Bourbonnais (long-time enthusiast of our brave Bourbonnais). It was published in the Bourbonnais Club bulletin in 1933, and details Dubut’s efforts to reverse the errors of the past.

When I started breeding Braques du Bourbonnais 30 years ago, the dogma of absolute purity of the breed was the official, intangible doctrine of dog breeding, and the greatest achievement was to blend together all the champions of the breed, or at least their offspring. In a few years, I had assembled in my kennel the blood of all the kings and queens of the breed, but the more I concentrated my aristocratic stew, the more troubling faults I saw. Such a high level of inbreeding quickly becomes dangerous. Some of the few famous individuals of the breed, even though they are champions, have physical or mental faults that make it very dangerous for any linebreeding or inbreeding. That was the situation in my kennel around 1908. It was obvious to me that only crossbreeding could improve, revive, and save my Braque du Bourbonnais.

Unfortunately, despite the measures taken by Dubut and others, the breed continued to struggle throughout the early 1900s, and was almost wiped out during the First World War. But in 1925 the remaining supporters managed to create a club for the breed and establish a formal written standard.

For the next decade, things improved as breeders worked to overcome the difficulties of the past. Then the Second World War dealt an even more devastating blow and the postwar years did not prove much easier. Infighting among club members over the coat color and other minor details eventually caused so many problems that the club fell apart, breeding ground to a halt and registrations fell to a trickle. In 1967 Jean Castaing wrote that he had probably seen the last of the breed.

In the 1970s the man who would lead the effort to recreate the breed entered the scene. Today Michel Comte is known as the father of the modern Braque du Bourbonnais, but back then he was considered a dreamer, attempting the impossible.

I come from a family of hunters. My father and grandfather hunted mainly with running hounds, but we had a Braque d’Auvergne as well. When I was about 16 or 17 years old, I got the idea that it would be nice to have a Braque du Bourbonnais. I was fascinated by the unique lilas passé [faded lilac] color of its coat. I dreamed for many years about owning such a dog. But everyone told me not to bother; the breed was dead. Then one day I just said: To heck with them, I will recreate it!

Among the first steps Michel took was to seek the advice of dog expert Jean Castaing who he visited at Castaing’s summer home near the town of Agen. Unfortunately, the great man did not offer much hope.

Basically, [Castaing] told me,“You are a nice

guy but you are a dreamer. Reviving the breed is impossible.” And, I must admit, he was right. Revival was out of the question. But we could try to recreate it, and that is what we did!

Efforts to create the modern Braque du Bourbonnais began in earnest when Michel, assisted by his brother, Gabriel; Dr. Louis Monavon, a local veterinarian and other enthusiasts decided to see if they could find any remaining dogs of the Bourbonnais type. They combed through back issues of hunting magazines and newspapers looking for the names of former breeders to contact. To their dismay, they discovered that the breed had been more or less abandoned by its former supporters and all the breeders had moved on to the more popular German Shorthairs, English Pointers and Brittanies.

However, Dr. Monavon would sometimes see dogs in his veterinary practice that closely resembled Braques du Bourbonnais. They were mixed-breed dogs that their owners simply referred to as braques du pays (country braques). But the dogs had many of the characteristics of the original Braque du Bourbonnais, such as the naturally short tail, unique coat color and head shape. So Michel and his group decided to use some of these braques du pays in a program designed to distill and concentrate the genes of the original breed. One of the most important dogs used in the program was named Pyrrhus. Michaël Comte, Michel’s son, tells its story:

One day Dr. Bazin, the president of the south-east Canine Society, discovered a handsome “peach blossom” [fawn colored] dog in Lyon. It was an offspring of Joséphine and Napoléon,

two dogs belonging to the famous French singer Pierre Perret, that were registered as German Shorthairs! You see, at the time, breeders did their own paperwork and the SCC [French Canine Society] just rubber-stamped the pedigrees. So that is probably how a Braque du Bourbonnais ended up with “German Shorthair” parents. In any case, Pyrrhus was entered into the stud book under the name Rasteau. He was the first in a long line of born-again Bourbonnais.

Toward the end of the 1970s, the breeding efforts of the small group began to bear fruit. For the first time in over a decade, Braques du Bourbonnais were being registered in the French stud book (LOF) and the numbers were increasing every year. By the 1980s organized events were taking place and more and more Braques du Bourbonnais were seen in the show ring and field trials.

Today, the breed continues to thrive. Although growth has slowed in France, the Braque du Bourbonnais has gained a firm foothold in the US where there are now just as many, and sometimes even more, Bourbonnais pups whelped each year. Michel Comte told me: The breed is still a work in progress. It is a recreated breed, a synthesis of the old stock we found and the new blood we added. Castaing was right: it was impossible to bring the old Braque du Bourbonnais back to life. But what we have today is in many ways better than the original. They are faster, stronger, better hunting dogs than they used to be.

WHAT'S IN A NAME

Brak Doo Boor-Bon-Nay

The breed is named after the historic province of Bourbonnais in central France. The English translation in the breed standard is Bourbonnais Pointing Dog, but breeders everywhere usually use the French name.

MY VIEW

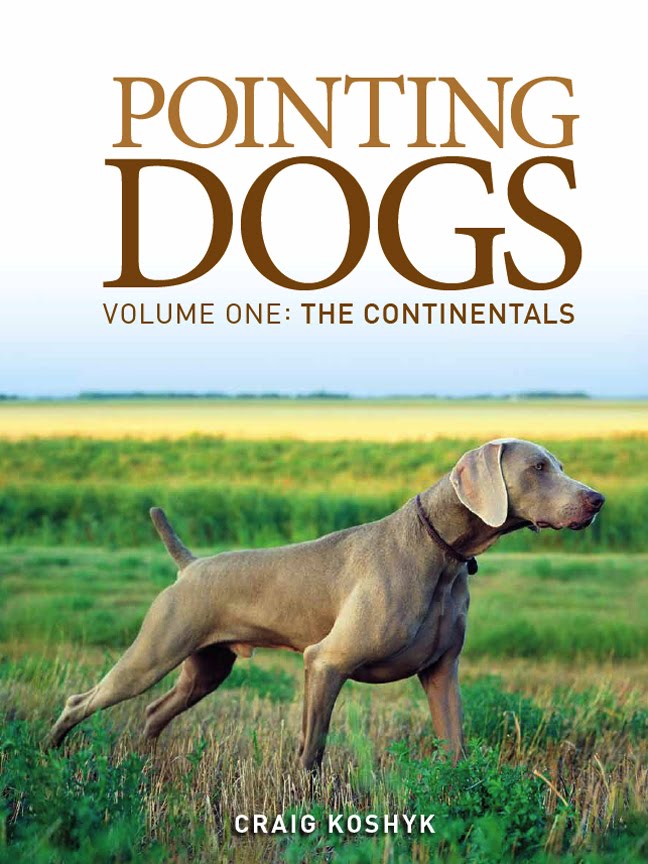

I have had the opportunity to see a number of Braques du Bourbonnais in action in France, as well as in Québec and Ontario. They definitely have a unique look. They are relatively small, not much bigger than a Brittany, but some of them can be built like fireplugs. The Bourbonnais’ coat really is something special. The heavy ticking and nearly pastel coloring is a great combination. The stubby tail and rounded head complete the package. In the field, every Bourbonnais I’ve seen was an eager worker, light on its feet and solid on point. But beyond the look and field abilities of the breed, there is something very special about the Braque du Bourbonnais: the man who led the effort to recreate it.

Lisa and I met Michel Comte at his home on the Côte d’Azur and we were fascinated by the stories he had to tell. As he spoke about his beloved breed his eyes sparkled with a rare light that we had seen in very few others. And as he reminisced about the great dogs he’d bred in the past and spoke proudly about the young prospects he was raising today, I kept thinking back to what he said when I asked him how it all started:

I dreamed for many years about owning such a dog. But everyone told me not to bother; the breed was dead. Then one day I just said: To heck with them, I will recreate it!

Later that day as we photographed his dogs in the field, I realized that we were in the presence of a great man, a man who had fulfilled his dream by achieving the near-impossible. Michel Comte and a small group of dedicated hunters brought an ancient breed of pointing dog back to the fields and forests where it belongs. And a growing number of hunters will forever be grateful they did.

To learn more about the breed, visit Michael Comte's excellent website for the breed

here.