Breed of the Week: The Weimaraner Part 1

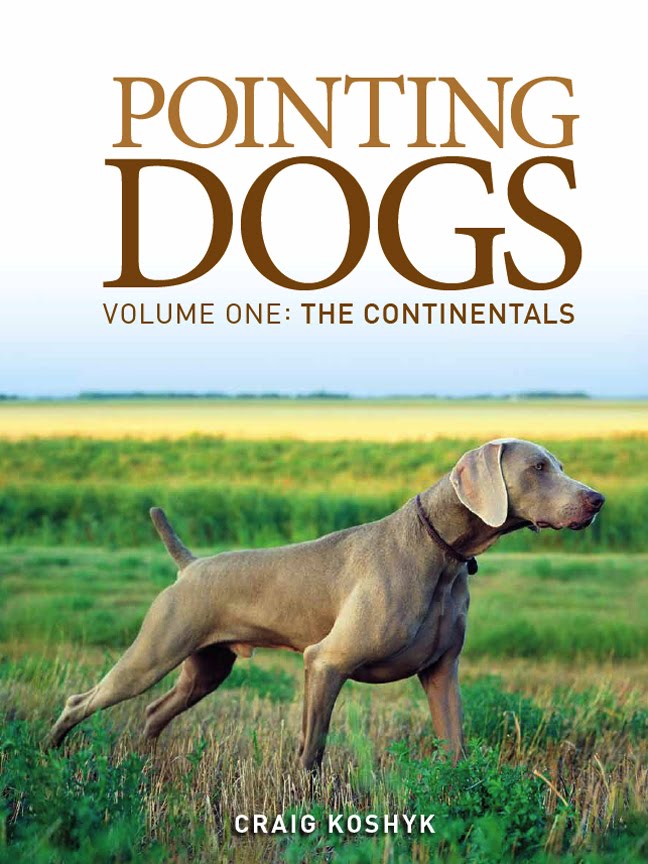

Craig Koshyk

Over the next three weeks, the Breed of the Week will feature a versatile gundog that is very close to my heart - the Weimaraner. I've decided to devote extra time to the Weim for a couple of reasons. First of all, I hope that sharing the story of this fascinating German hunting breed might serve as a wake-up call to other breeds that are on the slippery slope of beauty over ability. But more importantly, I want to make it very clear to hunters that despite the Weimaraner's reputation as a less than stellar performer in the field, there are in fact some awesome hunting Weims out there. With a little homework, you really can find a Weim that is as good as any other versatile hunting dog on the planet.

Readers of this blog are probably familiar with my views on the Weimaraner. I have written about it since I started the blog in 2006 and have gone off on a few rants like this one here, here and here. But when it came time to write the chapter on the breed in my book, I dialled the rhetoric down a notch.

Despite the fact that I am very familiar with the breed—I own Weimaraners and spend an average of about 50 days per season hunting with them—writing this chapter was more difficult than I had anticipated. It was not due to any lack of information, resources or access to breed experts. The hard part was resisting the urge to rant about the sorry state of the breed in much of the world today.

Nevertheless, if I could only say one thing about Weimaraners, it would be this: they can be awesome gundogs. If you take the time to look around, you can find a Weimaraner that any hunter would be proud to own.

I have been very fortunate that all my Weimaraners have turned out to be good workers. The handsome fellow on the cover of this book is Félix, my very first hunting dog. The best thing about him was his drive, nose and unwavering loyalty. The worst thing about him was that he was way too smart for his own good. Training him was like trying to debate astrophysics with Steven Hawking. Since then, I have had other Weims, short-haired and long-haired, and they’ve all been excellent hunters. They’ve all come from breeders who hunt as much as I do and look for the same things in a gundog as I do: desire, speed, point, nose, and a love of water.

Ten years ago, I got a pup from Dick Wilber, a straight-talking Texan who has proven his dogs in the highest levels of competition. That pup turned out to be an absolutely “out of the box” dog. She literally trained herself. All I did was take her hunting and keep my mouth shut. I’ve hunted more days over my Souris than over any other dog, and I truly believe she may be my once-in-a-lifetime hunting partner. My other Weims include a long-haired bitch I imported from Germany, and an absolute rocket of a Weim from my friend Judy Balog. I hope those two will be the foundation of my very own line.

Ten years ago, I got a pup from Dick Wilber, a straight-talking Texan who has proven his dogs in the highest levels of competition. That pup turned out to be an absolutely “out of the box” dog. She literally trained herself. All I did was take her hunting and keep my mouth shut. I’ve hunted more days over my Souris than over any other dog, and I truly believe she may be my once-in-a-lifetime hunting partner. My other Weims include a long-haired bitch I imported from Germany, and an absolute rocket of a Weim from my friend Judy Balog. I hope those two will be the foundation of my very own line.

Since the breed suffers from a fairly poor reputation among hunters, especially in the US and Canada, I have been on the receiving end of some nasty remarks when people find out I have Weims. But I am happy to say that I have shown many naysayers the error of their ways. I remember one fellow in particular who could not talk enough trash about the breed when we first met. But after spending an afternoon hunting over my dogs, he apologized for his disparaging remarks, and asked to be put on the waiting list for a pup!

I have heard similar stories from others in North America who are working to keep the hunt in the breed and to convince other hunters to join their cause. Recently, an alliance has been formed among field-oriented breeders to do just that. It is still the early days for a group that exists mainly online at www.huntingweimforum.com, but they are taking a giant step in the right direction. Hopefully, their efforts will lead to a better awareness among American and Canadian hunters that Weimaraners from proven lines can make excellent hunting partners.

So how did the Weim end up being at the bottom of the V-dog totem pole when it comes to the ratio of good to bad workers in the breed? Well, it turns out that the story of the Weimaraner has all the elements of a Hollywood melodrama. It is a classic tale of how marketing, money and the vain pursuit of blue ribbons can turn a noble breed of hunting dog into a caricature of its former self. Fortunately, like any good melodrama, there’s a happy ending. Despite the challenges the breed continues to face, there are still dedicated Weimaraner breeders out there producing world-class gundogs.

The official history of the Weimaraner begins on June 22, 1897 when a club for the “pure breeding of the silver-grey Weimaraner pointing dog” was formed in Erfurt, Germany. The breed’s development since that time is relatively well documented. The historical record from before that time is much less clear. And since the further back it goes, the fuzzier it gets, all we have are theories based almost entirely on speculation.

Despite the fact that I am very familiar with the breed—I own Weimaraners and spend an average of about 50 days per season hunting with them—writing this chapter was more difficult than I had anticipated. It was not due to any lack of information, resources or access to breed experts. The hard part was resisting the urge to rant about the sorry state of the breed in much of the world today.

Nevertheless, if I could only say one thing about Weimaraners, it would be this: they can be awesome gundogs. If you take the time to look around, you can find a Weimaraner that any hunter would be proud to own.

I have been very fortunate that all my Weimaraners have turned out to be good workers. The handsome fellow on the cover of this book is Félix, my very first hunting dog. The best thing about him was his drive, nose and unwavering loyalty. The worst thing about him was that he was way too smart for his own good. Training him was like trying to debate astrophysics with Steven Hawking. Since then, I have had other Weims, short-haired and long-haired, and they’ve all been excellent hunters. They’ve all come from breeders who hunt as much as I do and look for the same things in a gundog as I do: desire, speed, point, nose, and a love of water.

Ten years ago, I got a pup from Dick Wilber, a straight-talking Texan who has proven his dogs in the highest levels of competition. That pup turned out to be an absolutely “out of the box” dog. She literally trained herself. All I did was take her hunting and keep my mouth shut. I’ve hunted more days over my Souris than over any other dog, and I truly believe she may be my once-in-a-lifetime hunting partner. My other Weims include a long-haired bitch I imported from Germany, and an absolute rocket of a Weim from my friend Judy Balog. I hope those two will be the foundation of my very own line.

Ten years ago, I got a pup from Dick Wilber, a straight-talking Texan who has proven his dogs in the highest levels of competition. That pup turned out to be an absolutely “out of the box” dog. She literally trained herself. All I did was take her hunting and keep my mouth shut. I’ve hunted more days over my Souris than over any other dog, and I truly believe she may be my once-in-a-lifetime hunting partner. My other Weims include a long-haired bitch I imported from Germany, and an absolute rocket of a Weim from my friend Judy Balog. I hope those two will be the foundation of my very own line.Since the breed suffers from a fairly poor reputation among hunters, especially in the US and Canada, I have been on the receiving end of some nasty remarks when people find out I have Weims. But I am happy to say that I have shown many naysayers the error of their ways. I remember one fellow in particular who could not talk enough trash about the breed when we first met. But after spending an afternoon hunting over my dogs, he apologized for his disparaging remarks, and asked to be put on the waiting list for a pup!

I have heard similar stories from others in North America who are working to keep the hunt in the breed and to convince other hunters to join their cause. Recently, an alliance has been formed among field-oriented breeders to do just that. It is still the early days for a group that exists mainly online at www.huntingweimforum.com, but they are taking a giant step in the right direction. Hopefully, their efforts will lead to a better awareness among American and Canadian hunters that Weimaraners from proven lines can make excellent hunting partners.

The official history of the Weimaraner begins on June 22, 1897 when a club for the “pure breeding of the silver-grey Weimaraner pointing dog” was formed in Erfurt, Germany. The breed’s development since that time is relatively well documented. The historical record from before that time is much less clear. And since the further back it goes, the fuzzier it gets, all we have are theories based almost entirely on speculation.

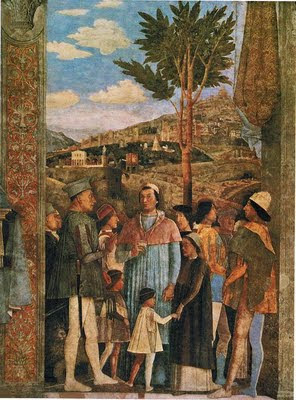

While researching the history of the breed for the book, I looked at several of the most common theories and found gaping holes in most of them. The "Grey Dogs of King Louis Theory" for example suggests that Weims descend from dogs known as Chiens Gris (grey dogs) brought back from the orient by King Louis of France hundreds of years ago.

What supporters of this theory conveniently overlook is that the word gris does not refer to the dilute brown shade that gives the Weimaraner its unique color. In the modern standards for the Griffon, Picardy Spaniel and other breeds, the term gris (and “grey” in the English translation) is used to describe the tight mix of white and brown hairs in their coat. What’s more, the best of King Louis’ dogs were actually said to be tri-colored with gris (brown and white) and/or black along the back and red markings on the legs.

The other most commonly held theory is that the breed was created by the Grand Duke Charles August of Weimar. However, there is exactly ZERO evidence to support the theory. Personally, I don't think the Grand Duke had anything to do with the breed at all and I would challenge anyone who claims he did to provide evidence to support their position. So far no one has taken up the challenge. I wrote about the Grand Duke theory here.

After digging as deep as I could into the history of the breed, I came to the conclusion that the theory that makes the most sense, is the "GSP Theory". It is one of the more controversial theories and was first proposed around 1900 by several authorities. They claimed that the Weimaraner was either a grey version of the GSP, or that it was created in much the same way as the GSP: by crossing heavy old-style German dogs with English Pointers. Karl Brandt, a founding member of the Weimaraner club, supported this theory, as did a Dr. A. Stoese, who wrote in 1902 that the Weimaraner descended from a yellow and white smooth-haired English Pointer bitch imported into Germany in the 1820s. Unlike the other theories, the GSP theory is actually supported by some fairly good circumstantial evidence. Several eyewitnesses attest to the fact the Weimaraner was quickly transformed from a large, lumbering tracking hound into a sleek pointing dog.

After digging as deep as I could into the history of the breed, I came to the conclusion that the theory that makes the most sense, is the "GSP Theory". It is one of the more controversial theories and was first proposed around 1900 by several authorities. They claimed that the Weimaraner was either a grey version of the GSP, or that it was created in much the same way as the GSP: by crossing heavy old-style German dogs with English Pointers. Karl Brandt, a founding member of the Weimaraner club, supported this theory, as did a Dr. A. Stoese, who wrote in 1902 that the Weimaraner descended from a yellow and white smooth-haired English Pointer bitch imported into Germany in the 1820s. Unlike the other theories, the GSP theory is actually supported by some fairly good circumstantial evidence. Several eyewitnesses attest to the fact the Weimaraner was quickly transformed from a large, lumbering tracking hound into a sleek pointing dog.

In the end, it is fair to say that we will never know just how the Weimaraner came to be. But the fact that so much ink was spilled trying to come up with a plausible back story is very revealing. It shows that breed supporters knew they had to convince the dog establishment that the Weimaraner was not just another recent creation or a grey version of the GSP. They had seen how a breed known as the Wurttemburger was eliminated as an unwanted color variety of the GSP and feared the same thing would happen to the Weimaraner. So, they published all kinds of stories about the breed’s supposed noble past and its connections to royal dogs from France.

In the end, it is fair to say that we will never know just how the Weimaraner came to be. But the fact that so much ink was spilled trying to come up with a plausible back story is very revealing. It shows that breed supporters knew they had to convince the dog establishment that the Weimaraner was not just another recent creation or a grey version of the GSP. They had seen how a breed known as the Wurttemburger was eliminated as an unwanted color variety of the GSP and feared the same thing would happen to the Weimaraner. So, they published all kinds of stories about the breed’s supposed noble past and its connections to royal dogs from France.

They went on and on about how pure the Weimaraner was and even presented pseudo-scientific “studies” based on crackpot theories of Germanic head shapes and other nonsense. Surprisingly, it worked! After nearly 20 years, the Delegate Commission recognized the Weimaraner as a separate and independent breed. Nevertheless, from 1897 to 1922, Weimaraners did not have their own registry, but were listed in the German Shorthaired Pointer’s stud book. Dr. Werner Petri wrote about the system then in place:

|

| Chien Gris de Saint Louis |

What supporters of this theory conveniently overlook is that the word gris does not refer to the dilute brown shade that gives the Weimaraner its unique color. In the modern standards for the Griffon, Picardy Spaniel and other breeds, the term gris (and “grey” in the English translation) is used to describe the tight mix of white and brown hairs in their coat. What’s more, the best of King Louis’ dogs were actually said to be tri-colored with gris (brown and white) and/or black along the back and red markings on the legs.

After digging as deep as I could into the history of the breed, I came to the conclusion that the theory that makes the most sense, is the "GSP Theory". It is one of the more controversial theories and was first proposed around 1900 by several authorities. They claimed that the Weimaraner was either a grey version of the GSP, or that it was created in much the same way as the GSP: by crossing heavy old-style German dogs with English Pointers. Karl Brandt, a founding member of the Weimaraner club, supported this theory, as did a Dr. A. Stoese, who wrote in 1902 that the Weimaraner descended from a yellow and white smooth-haired English Pointer bitch imported into Germany in the 1820s. Unlike the other theories, the GSP theory is actually supported by some fairly good circumstantial evidence. Several eyewitnesses attest to the fact the Weimaraner was quickly transformed from a large, lumbering tracking hound into a sleek pointing dog.

After digging as deep as I could into the history of the breed, I came to the conclusion that the theory that makes the most sense, is the "GSP Theory". It is one of the more controversial theories and was first proposed around 1900 by several authorities. They claimed that the Weimaraner was either a grey version of the GSP, or that it was created in much the same way as the GSP: by crossing heavy old-style German dogs with English Pointers. Karl Brandt, a founding member of the Weimaraner club, supported this theory, as did a Dr. A. Stoese, who wrote in 1902 that the Weimaraner descended from a yellow and white smooth-haired English Pointer bitch imported into Germany in the 1820s. Unlike the other theories, the GSP theory is actually supported by some fairly good circumstantial evidence. Several eyewitnesses attest to the fact the Weimaraner was quickly transformed from a large, lumbering tracking hound into a sleek pointing dog.In my younger years, I saw (the Weimaraner) look like a German bloodhound with hanging lips and watering eyes, but now it has arrived at the form of the German Shorthair and so it has certainly changed for the better. (Carl Linke quoted by William Denlinger, The Complete Weimaraner, 36)

In the end, it is fair to say that we will never know just how the Weimaraner came to be. But the fact that so much ink was spilled trying to come up with a plausible back story is very revealing. It shows that breed supporters knew they had to convince the dog establishment that the Weimaraner was not just another recent creation or a grey version of the GSP. They had seen how a breed known as the Wurttemburger was eliminated as an unwanted color variety of the GSP and feared the same thing would happen to the Weimaraner. So, they published all kinds of stories about the breed’s supposed noble past and its connections to royal dogs from France.

In the end, it is fair to say that we will never know just how the Weimaraner came to be. But the fact that so much ink was spilled trying to come up with a plausible back story is very revealing. It shows that breed supporters knew they had to convince the dog establishment that the Weimaraner was not just another recent creation or a grey version of the GSP. They had seen how a breed known as the Wurttemburger was eliminated as an unwanted color variety of the GSP and feared the same thing would happen to the Weimaraner. So, they published all kinds of stories about the breed’s supposed noble past and its connections to royal dogs from France.They went on and on about how pure the Weimaraner was and even presented pseudo-scientific “studies” based on crackpot theories of Germanic head shapes and other nonsense. Surprisingly, it worked! After nearly 20 years, the Delegate Commission recognized the Weimaraner as a separate and independent breed. Nevertheless, from 1897 to 1922, Weimaraners did not have their own registry, but were listed in the German Shorthaired Pointer’s stud book. Dr. Werner Petri wrote about the system then in place:

In the early years, pups were not registered; and only dogs that had previously been shown at exhibitions or tested and evaluated. This was certainly necessary at the time since dogs had to be examined first to establish their “breed purity”, at least when it came to appearance. In the first few years the numbers of Weimaraners entered was from five to 19. In 1900, 62 dogs were registered, obviously en masse, since dogs with birth dates back to 1891 were included. In subsequent years, the entries were sparse, but then, in 1904, a record high of 121 were made. Here again many older dogs born in 1894 are found. Then, the registration numbers fall off strongly once more. From 1907 to 1913 there are no Weimaraners found in the stud book. In total, during the first ten volumes of the Deutsch Kurzhaar (GSP) stud book, 265 Weimaraners were registered.Dr. Petri goes on to explain that the increasing pressure to eliminate the grey coat color from the German Shorthaired Pointer led to some Weimaraners being refused entry into the stud book. As a result, many Weimaraner breeders stopped registering their dogs. This led to a decline in the number of dogs listed and to a decline in the overall population of the breed.

...it may be assumed that in these years the Weimaraner as a breed was nearing extinction. That was the fate of the Württemberg breed which, by being registered in the German Shorthaired Pointer stud book, went extinct or was absorbed into the German Shorthaired Pointer.PART TWO: The Weim bounces back...bigtime!!

Read more about the breed, and all the other pointing breeds from Continental Europe, in my book Pointing Dogs, Volume One: The Continentals