The Pudelpointer

Craig Koshyk

If you made a list of the pro's and con's of this week's breed of the week, the list of pro's would be very long indeed. And the list of con's might only have one thing on it: the breed's name.

Ask just about any Pudelpointer owner or breeder and they will tell you that having to explain the name of their breed gets old real fast. What drives them round the bend quickest is that fact that so many people, when they first hear the name, assume that the breed is some sort of modern designer dog like the Labradoodle or Puggle*. And unless they have the time to sit through a half hour power-point presentation on the history of dog breeding in Germany circa 1885 it is really hard to explain in a few sentences. I do my best to explain the name in the Pudelpointer chapter of my book and I also dig pretty deep into the history of the breed, in particular into the kinds of dogs that gave the breed the first part of its name, the so-called "Pudels."

Here is an excerpt from the history section:

Here is an excerpt from the history section:

In the late 1800s, English Pointers were enjoying great popularity across Europe and were well regarded for their tremendous speed and passion in the field. But what were the Pudels, Königspudels and Polish Waterdogs that Hegewald wrote about? Today, no one seems to know much about them. But in Hegewald’s time, everyone knew what they were. In fact, as far back as 1621, Englishman Gervase Markham wrote that:

The water dog is a creature of such general use…that it is needless to make any large description of him…since not any among us is so simple that he cannot say when he sees him: “This is a water dog.”

Fortunately, Markham then goes on to actually describe the water dog, saying that it:

...may be of any color and yet excellent, and his hair in general would be long and curled, not loose and shaggy; for the first shows hardness and ability to endure the water, the other much tenderness and weakness, making his sport grievous. His head would be round and curled, his ears broad and hanging, his eye full, lively and quick, his nose very short, his lip hound-like, side and rough-bearded, his chops with a full set of strong teeth, and the general features of his whole countenance being united together would be as lion-like as might be, for that shows fierceness and goodness…

The dogs Markham describes were probably the descendants of herding dogs that had long, thick coats to protect them from the elements and the strength and agility to work in the toughest conditions, including cold water. Everywhere they were found, they were crossed with other breeds, some of them short-haired. Hans Friedrich von Fleming gives us further details in the 1719 book Der Vollkommene Teutsche Jäger (The Complete German Hunter).

The shepherds have small or medium driving dogs, which have shaggy hair. Such Budels are now covered with a Hound, so the offspring fall with long ears and shaggy hair. In order that they swim better their thick hair is taken off, a good beard and eyebrows remain, and the tail is docked. Because of their beard, the French call them Barbet. These water dogs from the gray color of the Shepherd and the red hair of the Hound are mostly brown, though often white with brown spots, or even black. They are brisk and faithful, they hunt gladly, and they like by nature to swim. They retrieve well in reeds and fast rivers. They also hunt out foxes, otters, and wild cats from the reeds. Such a water dog is of great service to the fowler.

Rough-coated water dogs went by different names in different regions. They were often said to come from Russia, Poland or Bohemia. In all likelihood, they didn’t develop in just one region since they were found across much of the continent. The names they were given were probably based more on stereotypes than the dogs’ actual origins. Jean Castaing suggests that the English called them Russian for the same reason the Germans called them Polish; because they had a rough, unkempt appearance that was considered typical of Eastern European people at the time.

Here is an excerpt from the "my view" section of the chapter:

Compared to many other breeds of gundogs, Pudelpointers are rare. Yet Lisa and I have seen them in Germany, France, Slovakia, the Czech Republic, the US and Canada. We’ve even hunted over a few right here in our home province of Manitoba.

Compared to many other breeds of gundogs, Pudelpointers are rare. Yet Lisa and I have seen them in Germany, France, Slovakia, the Czech Republic, the US and Canada. We’ve even hunted over a few right here in our home province of Manitoba.

Our frequent contacts with the breed are due to the fact that when we travel to photograph dogs or to hunt, we tend to meet people that are just as passionate about hunting as we are. Since the breed is and always has been in the hands of hunters, it stands to reason that we would come across more Pudelpointers in a couple of seasons than the average dog walker at a local park would see in a lifetime.

I’ve seen North American-bred and German Pudelpointers. I’ve run my dogs in fun trials and training sessions with an excellent Pudelpointer owned by one of the guys in our local pointing dog club. And I remember a fantastic photo shoot in Ontario with Pudelpointers that hit the water like Labs. In all of these encounters, I never felt the least bit intimidated by any of the dogs. Every Pudelpointer I have ever met has been an easygoing, friendly dog whether it was in the house, in a camper or staked out beside a truck. In the field, they all hunted hard. Sure, some were faster and bigger-running than others. Some were also better looking than others—I can confirm the variation in coat quality in the breed—but not a single one of them left me with any doubt about their hunting desire.

I’ve seen North American-bred and German Pudelpointers. I’ve run my dogs in fun trials and training sessions with an excellent Pudelpointer owned by one of the guys in our local pointing dog club. And I remember a fantastic photo shoot in Ontario with Pudelpointers that hit the water like Labs. In all of these encounters, I never felt the least bit intimidated by any of the dogs. Every Pudelpointer I have ever met has been an easygoing, friendly dog whether it was in the house, in a camper or staked out beside a truck. In the field, they all hunted hard. Sure, some were faster and bigger-running than others. Some were also better looking than others—I can confirm the variation in coat quality in the breed—but not a single one of them left me with any doubt about their hunting desire.

For me, the bottom line on Pudelpointers is this: they are the real deal; they are dynamic hunting dogs bred by and for hard-core hunters.

* I can understand why Pudelpointer owners bristle. Labradoodles are now everyone's punching bag for what is wrong with the "designer dog" breeds. But there are some valid parallels to be made between the two. First of all, both started off as a brilliant idea, supported by men of vision who were seeking to created something greater than the sum of its parts. Of course we can now say that Pudelpointer succeeded and that the Labradoodle did not. Even the man who did the first crosses of Labs and Poodles eventually disowned the Labradoodle "breed" due to all the hucksters who jumped on the bandwagon. Secondly, both breeds are a combination of a smooth haired breed and a curly haired breed and generally produce wirehaired pups. And finally, both breeds' names are a combination of the names of the two breeds that they were created from.

The story of the Labradoodle is actually quite tragic. What started out as a good idea (hypoallergenic guide dogs for the blind) ended up being a victim of a modern dog breeding culture dominated by money, greed and ego. The Pudelpointer on the other hand was developed during the golden age of dog breed creation, when there was still a sense of honor and purpose among many of the leading dog breeders.

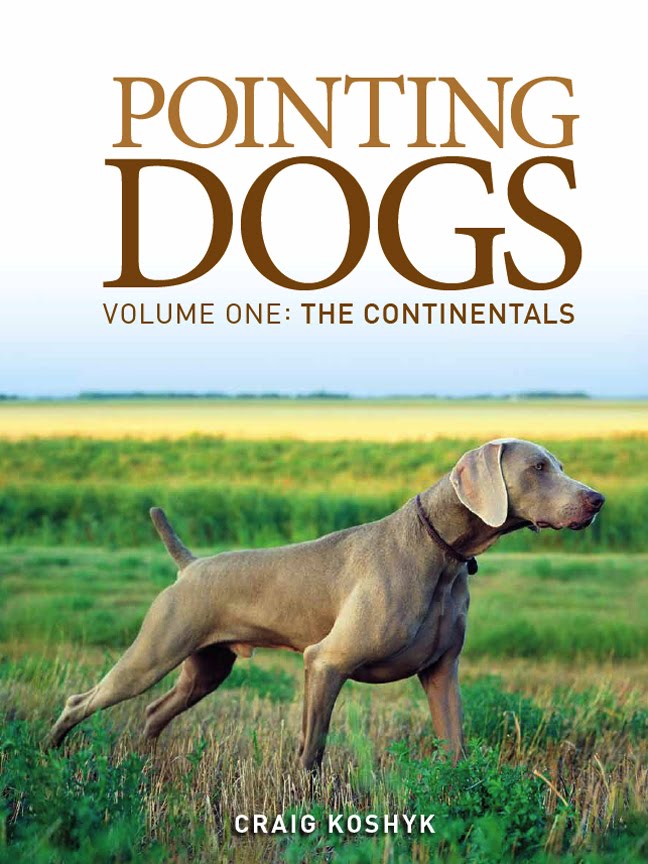

Read more about the breed, and all the other pointing breeds from Continental Europe, in my book Pointing Dogs, Volume One: The Continentals

The story of the Labradoodle is actually quite tragic. What started out as a good idea (hypoallergenic guide dogs for the blind) ended up being a victim of a modern dog breeding culture dominated by money, greed and ego. The Pudelpointer on the other hand was developed during the golden age of dog breed creation, when there was still a sense of honor and purpose among many of the leading dog breeders.

Read more about the breed, and all the other pointing breeds from Continental Europe, in my book Pointing Dogs, Volume One: The Continentals