Mystery Breed?

Craig Koshyk

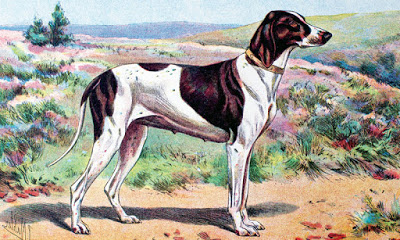

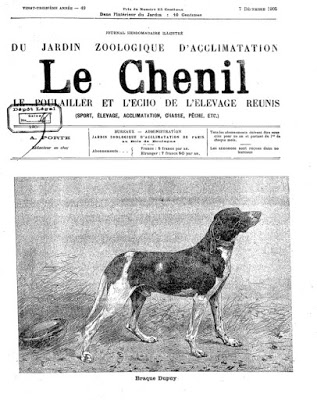

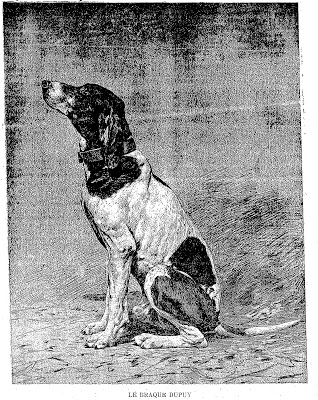

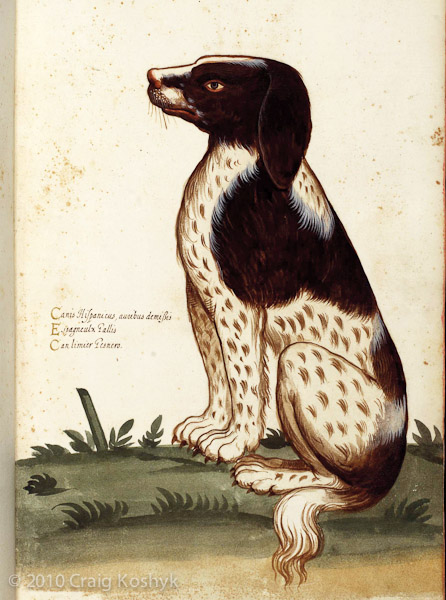

Charles Fernand de Condamy (1847-1913) was a well-known watercolour painter in France in the late 1800s. If you do a google image search for his works, among all the wonderful painting of horses and hounds, is this shot of a dog on point.

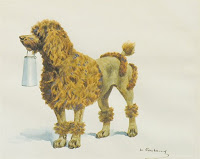

Well, I don't think it is a Poodle. Here is how de Condamy painted that breed.

And it is probably not an Irish Water Spaniel. After all, that breed doesn't point... or DOES IT? Have a look at this video. It is of an Irish Water Spaniel and a Boykin Spaniel hunting pheasants in Oregon.

Now, let's compare that to what I wrote about our Ponto Uma in my book:

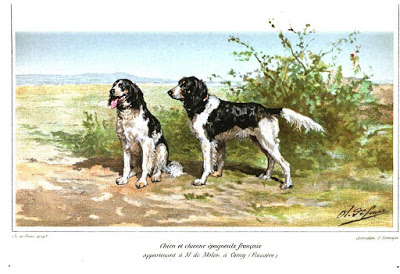

Be that as it may, my guess is that the dog in De Condamy's watercolour painting is indeed a Pont-Audemer Spaniel. The artist lived and hunted in the north of France were Pontos were relatively common in his day. It is very likely that he'd hunted over them and knew hunters who bred and owned Pontos. So, until and unless more evidence comes to light that indicates otherwise, we can enjoy the lovely painting as an extremely rare image of a Ponto on point from the 1880s.

Enjoy my blog posts? Check out my book Pointing Dogs, Volume One: The Continentals

|

| Charles-Fernand de Condamy |

What is unusual about the image is that it shows a dog with a curly coat, and there is only one breed of pointing dog that has such a coat, the Pont-Audemer Spaniel. But as far as I can tell, the painting does not have a title. At auction, it has been listed as an image of an Irish Water Spaniel and/or Pont-Audemer Spaniel. One auction site even listed it as a watercolour painting of a Poodle.

De Condamy's painting may have also inspired one of French sculptor Albert Laplanche's bronzes. Unfortunately the small statue is simply listed as "Chien à l'arrêt" (dog on point), so we still have no solid confirmation of what breed it is. So what breed could de Condamy's watercolour represent?

|

| Chien à l'arrêt by Albert Laplanche |

And it is probably not an Irish Water Spaniel. After all, that breed doesn't point... or DOES IT? Have a look at this video. It is of an Irish Water Spaniel and a Boykin Spaniel hunting pheasants in Oregon.

I asked the owner of the Irish Water Spaniel about the dog in the video and this is what he told me:

Ah yes, the hesitation flush (aka the point). With my limited experience of hunting with only 3 IWS, my speculation has two parts. One is that IWS are somewhere on the continuum between a flusher and a pointer and as such, they can be trained to go either way depending on the individual dogs personality.

Tooey is a very reserved dog and if prey is not running, her chase instinct gets confused and so she points while determining what to do next. My male Cooper was an opportunist, and if he saw a hint of a bird, he would do anything to trap the bird before it flushed (we always got several birds each year that never left the ground). But if he winded a bird but could not see it at first, he would lock up while his brain processed what to do next. My youngest male recently saw a pheasant deep in wild rose and locked up tight, in a classic pointer pose. But when he encounters a moving bird, his prey drive kicks in.

The second speculation is that as the dogs confidence grows with experience, the tendency to point or hesitate at the flush diminishes over time. Tooey hesitates less and less, and only if the bird is in sight but not moving will it cause a point before the flush (she failed a senior level hunt test for this behavior but has never failed to find a downed bird or an crippled runner). However, the hesitation flush, or temporary point, has been a blessing for my shooting. Just having a few moments to prepare for the shot has allowed me to connect with birds that I probably would have missed with an instant flush. Not good for hunt tests, but great for the average shooter who likes to eat birds.

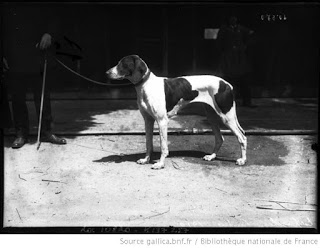

Now, let's compare that to what I wrote about our Ponto Uma in my book:

Uma lives to run and runs for fun. To her, pointing birds is great sport. But so is flushing and chasing them. When she was young, I tried to cure her of bumping and chasing in the same way I cured our Weimaraners. I took her to a field loaded with meadowlarks and let her chase for as long as she wanted. But it didn’t work. When our other dogs were young pups, they were given the same treatment but they quickly figured out that they could not catch the birds, so they stopped chasing them and started pointing. Not Uma. The more she bumped and chased, the more she enjoyed it. She was so driven to play this game, I was concerned that she would run till she dropped dead. Eventually, by adjusting my training methods, I managed to bring out her pointing instinct while discouraging her impulse to flush. Uma is now a very reliable pointer and even backs other dogs on her own.

I now believe that what Uma showed me early on was the basic conflict in the genetic makeup of the breed. With training she learned to listen to her pointing instinct and ignore the urge to flush. However, it could have gone the other way. It would have been very easy to train her to work like a Springer Spaniel.

Be that as it may, my guess is that the dog in De Condamy's watercolour painting is indeed a Pont-Audemer Spaniel. The artist lived and hunted in the north of France were Pontos were relatively common in his day. It is very likely that he'd hunted over them and knew hunters who bred and owned Pontos. So, until and unless more evidence comes to light that indicates otherwise, we can enjoy the lovely painting as an extremely rare image of a Ponto on point from the 1880s.

|

| Uma the Ponto on point! |

Enjoy my blog posts? Check out my book Pointing Dogs, Volume One: The Continentals