Breed of the Week: The Russian Setter

Craig Koshyk

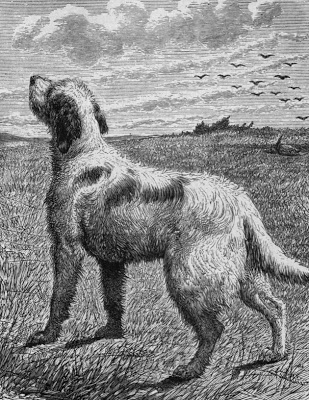

In October 1823, an illustration of a rough-haired dog retrieving a pheasant appeared on the cover of the The Sporting Magazine. The caption beneath the image read “Basto, A Russian Setter”. A description of Basto appears inside.

Basto is of Russian parents, which were highly valued in this country, and their offspring has in no way disgraced the character of these setters! He is distinguished in the lower parts of Surrey and in Sussex as an excellent finder, and of very delicate mouth. Basto brings his game, and has scarcely ever been known to lose a wounded bird, in either corn, furze, or water, which he takes and hunts with the same ease as a smooth-haired pointer hunts a stubble! Basto, like all sporting dogs of Russian blood, is slow, but he often picks up birds, hares, and pheasants, that a fast-hunting pointer has passed in the field. He is about eight years old, and the property of T. Gilliland, Esq.

References to the Russian Setters are relatively common in 19th century English sporting literature, but they are often so highly polarized and contradictory that it is hard to form an accurate picture of what they were really like. In terms of appearance, John Henry Walsh, also known as Stonehenge wrote that:

The actual form of the Russian Setter is almost entirely concealed by a long woolly coat, which is matted together in the most extraordinary manner. He has the bearded muzzle of the Deerhound and Scotch Terrier but the hair is of a more woolly nature, and appears to be between that of a Poodle and the water spaniel

Robert Leighton, who also mentions a “Russian Retriever” in the New Book of the Dog , says of the Russian Setter that:

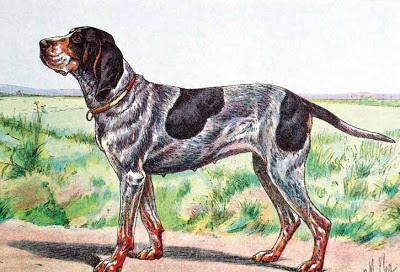

There are two varieties of the breed and, curiously enough, they are distinguished from each other by the difference in their color. The dark-colored ones are deep liver and are curly-coated. The light colored ones are fawn, with sometimes white toes and white on the chest; sometimes the white extends to a collar on the neck. These latter are straight-coated, not curly like the dark ones.Some descriptions read as if they were written by men who had never laid eyes on a Russian Setter. In Biographical Sketches and Authentic Anecdotes of Dogs, Thomas Brown provides a summary of the breed that is clearly no more than bits and pieces taken from descriptions of other pointing breeds. He even seems to confuse Russia with Spain, claiming that the Russian Setter had a cleft nose and was called the 'Doublenosed Pointer'.

There is one peculiarity about him, which is, that his nose is so deeply cleft that it appears to be split in two, on which account he is termed in Russia the Doublenosed Pointer. His scent is said to be superior to that of the smooth dogs. This cleft nose is found to be inconvenient when he is beating in cover, as the face is apt to be torn where the brushwood is thick.Other descriptions were from more reliable sources such as Edward Laverack, the man who litterally wrote the book on setters.

Russian (behind) English and Irish Setters

These dogs are but little known in this country. The late Joseph Lang's I have repeatedly seen. Two of them were brought down by Mr. Arnold, of London, to my shooting quarters, Dunmaglass. He had given thirty guineas a-piece for them as puppies, and had them very carefully broken by an English keeper. They were not at all good specimens of the class, and, as working dogs, comparatively useless. So disgusted was he with them before he left, that he shot one, and gave the other away. I have never seen but one pure specimen, which was in the possession of the late Lord Grantley, at Rannoch Barracks, head of Loch Rannoch, Perthshire. This dog was a magnificent type of the Russian setter, buried in coat of a very long floss silky texture; indeed he had by far the greatest profusion of coat of any dog I ever saw.

They were good but most determined, wilful, and obstinate dogs, requiring an immense deal of breaking, and only kept in order and subjection by a large quantity of work and whip; not particularly amiable in temper, but very high-couraged and handsome, an enormous quantity of long silky white hair, and a little weak lemon colour about the head, ears, and body ; and their eyes completely concealed by hair.

'Old Calabar' got a brace of these puppies, had them well broken, and took them to France ; but, after shooting to them two seasons, and being disgusted with their wilfulness and savage dispositions (they would take no whip), sold them to a French nobleman for a thousand francs (40/.), and considered he had got well out of them.

Reading through the old literature, it is clear that the terms “Russian Setter” and “Russian Pointer” were used to describe any rough-coated pointing dog in Britain at that time. Similar, if not identical dogs were called Smousbaarden in the Netherlands, Griffons in France and Polish or Hungarian Water Dogs in Germany. Before the late 1800s, none of them were 'pure' or independent breeds. They just represented a type of dog that was found just about everywhere sportsmen took to the field. A rough coat was their most distinctive feature and it was probably the reason men in Britain called the dogs “Russian”. It was commonly believed that people from the frozen eastern regions, and their dogs, were rather hairy and unkempt. In an article from The Farmer's Magazine in 1836, we can see just how politically incorrect many of the writers were at the time.

We may perhaps have seen a dozen of these brutes, which, like the people whence they derived their grossly misapplied appellation, are very uncouth very rough, imperturbably stupid, and, by way of continuing the similarity to the greatest possible extent, will generally be found infected with loathsome vermin.Thomas Burgeland Johnson's description of what he called the "Russian Pointer" in the 1819 issue of The Shooter’s Companion equally negative.

Whether he be originally Russian is very doubtful; but he is evidently the ugliest strain of the water-spaniel species; and, like all dogs of this kind, is remarkable for penetrating thickets and bramble bushes, runs very awkwardly, his nose close to the ground (if not muzzle-pegged), and frequently springs his game. He may be taught to set, and so may a terrier, or any dog that will run and hunt, and even pigs, if we are to believe the story of Sir Henry Mildmay’s black sow; but to compare him with the animals which have formed the subjects of the two preceding chapters (setters and pointers), would be outrageous: nevertheless, I am not prepared to say, that out of a hundred of these animals, one tolerable could not be found; but I should think it madness to recommend the Russian Pointer to sportsmen, unless for the purpose of pursuing the coot or the water-hen.

Mixing Russian Setters with other breeds is sometimes mentioned. The results of a crosses "...between the Russian setter and the smooth pointer" are given in Dogs of the British Islands.

... I must admit that the Russian and pointer cross has produced dogs that for work could not well be surpassed. I may, perhaps, have been fortunate in the specimens seen, but do not speak from one or two, but many. In appearance, however, they are not to be compared to the thorough-bred pointer or setter, though more elegantly shaped than the Russian. There is another peculiarity in this breed worthy of notice. You may go back to the Russian with favourable results. I shot over a brace so bred on the moors last season, that would be hard to beat for range, keenness of scent, and sagacity.

... rarely or never met with in this country. Could they be procured, I think of all sporting dogs they are the most adapted for ordinary American shooting, and the best of all for beginners. They have less style, and do not range so high as the English or Irish dogs, but that is no disadvantage for America, where there is so much covert shooting.

The Russian Setter never really achieved the status of an independent breed of pointing dog. I must have been just as difficult to stabilize as any other strain of griffon. And without a British Eduard Korthals or Emmanuel Boulet to champion its cause and perfect its breeding, the Russian Setter soon faded from the scene.

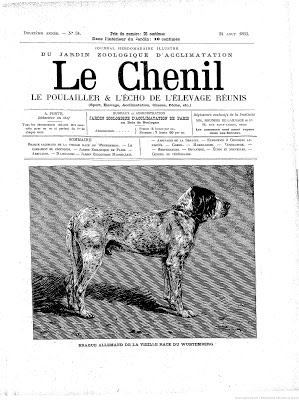

|

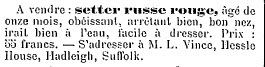

| Classified ad the French sporting newspaper Le Chenil, 1884. "For sale, Red Russian Setter, 11 months old, obedient, points well, good nose, works well in water, easy to train. Price: 55 Francs. Contact M. L. Vince, Hessle House Hadleigh, Suffolk Read more about the breed, and all the other pointing breeds from Continental Europe, in my book Pointing Dogs, Volume One: The Continentals |