The Drentsche Patrijshond a.k.a Dutch Partridge Dog

Craig Koshyk

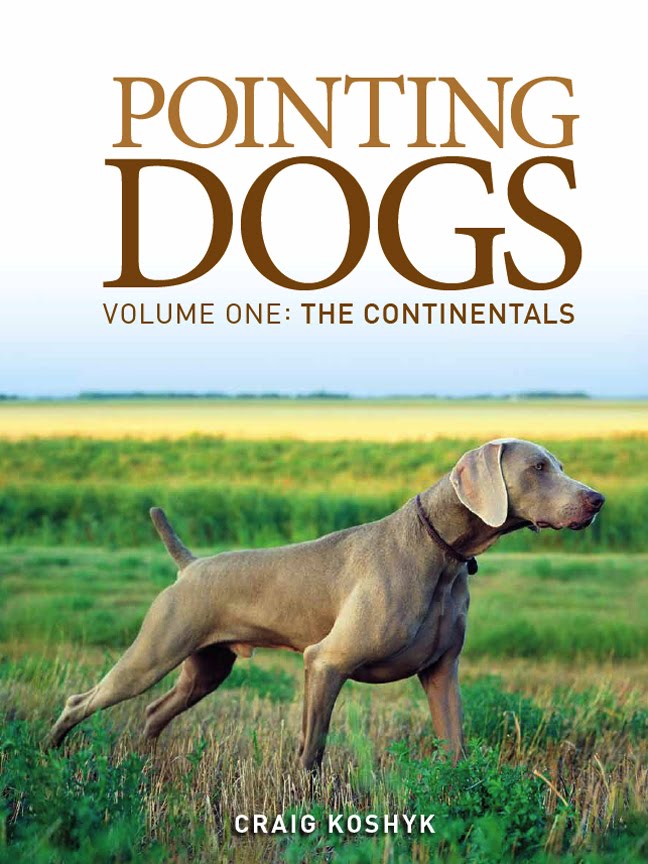

That, my friends is a nice looking dog. And I can tell you that he is a heck of a good hunter too!

Barak (yes, that's his name) is a Drentsche Patrijshond. He is Dutch born and bred and spends most of his time in the Netherlands chasing the surprisingly abundant game birds there. But I've actually seen Barak do his thing in France and in Canada as well as in his native land. And one day in particular really stands out in my memory.

We were hunting grouse and snipe in the Interlake area of Manitoba with Barak's people, Roel and Marjolein. I had my Pont-Audemer Spaniel Uma with me and Marjolein was handling Barak. As we made our way through a "bluff" of poplar trees, Barak slammed on point about 30 yards in front. Marjolein was about 40 yards to his right and began to move in. I heard Uma's bell coming towards me from the left. As she ran past she saw Barak and slammed into a back.

So there I was, rare French gun (a Darne) in hand, walking up to a rare Dutch breed of pointing dog that was being backed by an even rarer French breed of pointing dog. And to top it all off, instead of sharing the scene with one of my rough-around-the-edges hunting buddies and his beat up pump gun, my partner on the shoot that day was a beautiful Dutch woman carrying a fine over and under shotgun!

Like the English, Dutch hunters train their pointing dogs to flush on command and then stop for the shot. So when she got to within about 10 meters of Barak, Marjolein said something in Dutch that probably meant "get em up boy!" Instantly Barak made a bold charge toward the grouse and slammed on the breaks at the flush. The bird got up at the edge of the bluff and flew into a large open meadow offering me a perfect right to left crossing shot. I fired. It dropped. Marjolein yelled whatever the Dutch equivalent is for "Good Shot!" and Barak made the retrieve.

As he came towards us with the grouse, I realized that Mar and I had just witnessed something that no other hunter on earth has before or since: a Drentsche Patrisjond, backed by an Épagneul de Pont-Audemer pointing a ruffed grouse for a lovely Dutch woman and a curious Canadian fellow who really wanted a grouse for diner.

For more information on the Drentsche Patrijshond, check out the chapter on the breed in my new book or visit the website of the Drentsche Patrijshond Club of North America.

Read more about the breed, and all the other pointing breeds from Continental Europe, in my book Pointing Dogs, Volume One: The Continentals