Meanwhile in Picardy

The 1880s were a difficult time for the French pointing breeds. Nearly overwhelmed by a tsunami of Setters and Pointers, they were struggling to get their house in order. Lacking written breed standards, even official names for some breeds, judges had a hard time figuring out what was what in the show ring and how the various breeds should perform in the field. Even worse, a seemingly endless number of “rediscovered” breeds kept cropping up. After judging a dog show in Paris in 1884, Ernest Bellecroix published a plea for order.

Last year we were crushed under a completely unexpected number of classes. In all the species, native or foreign, new breeds, until now unknown, were discovered. There were 145 classes! Of all these different classifications, which one is the proper one? We have no idea. Therefore we request that the Society that has the difficult task of improving the breeds of dogs determines these breeds once and for all and clearly defines their characteristics. Even the owners of dogs sometimes had no idea what kind of dogs they owned or bred and often would enter them into the wrong class at a dog show or field trial.Meanwhile in Picardy, many of the locally bred dogs were of the French Spaniel or Pont-Audemer Spaniel type. They were medium sized, long haired dogs with white and brown or white and black coats and were said to be excellent workers in the field and water. However by the 1880s it was increasingly obvious that a hefty dose of British blood had made its way into most kennels.

Nowadays, the official story of how and why that happened goes something like this: wealthy British sportsmen would travel to northern France to hunt in the fall but then leave their Setters and Pointers with the locals for the winter since there was a quarantine back home. While they were away, their dogs would occasionally get lucky and have a fling with a local pointing dog and voila, suddenly a bunch of 'setterized' épagneuls and 'pointerized' braques were seen running around.

As plausible as it sounds, I've always found that story to be a bit too convenient. First of all, the quarantine act didn't come into effect until 1901. So for most of the 1800s British hunters could come and go as they pleased with their dogs. And secondly, it is well documented that a lot of French hunters were captivated by the beauty and abilities of the British dogs and would seize upon any opportunity to breed their dogs to them. French sportsman and dog expert, Adolphe De la Rue, actually witnessed the very beginning of the widespread and indiscriminate period of crossbreeding in France.

I remember that it was on one of the opening days, so noisy and numerous, that I saw for the first time a large black pointing dog of the kind that appeared in France in 1814 with the English army. The dog was so highly regarded that his owner did not know who to answer first. All of his neighbors had the dog cover their bitches, even if the bitches were épagneuls. Based on what I saw, I can conclude that these thoughtless crosses were taking place more or less everywhere, a dog of a foreign breed would appear, everyone would take a liking to it and want one of its kind.Clearly, the various setterized families of epagneuls in the north of France were not the results of happy accidents or illicit flings. They were intentionally created for the use and enjoyment of local hunters. In fact, there are even written records describing exactly how some of the families were created and in one case, an extraordinary colour illustration of what some of the first crosses may have looked like.

In an 1885 article published in Le Chenil a M. DE TOURIGNY wrote about tri-coloured dogs that were entered as French Spaniels in a number of shows and were awarded first place several times. (*translation mine, original French version below)

In 1883 at the Tuileries dog show two black and white spaniels with tan points were shown as French Spaniels. These two dogs, Odett and Kroumir 1 won first and second place in the class.

At the time, we criticized the decision, noting that these animals were not of the French Spaniel type; they were more like watered-down versions of English Setters, obviously the result of cross breeding or inadequate selection. This year, Odett was again shown with her son Kroumir II and five puppies, and won again. And yet we still failed to find any more of the French Spaniel type in Odett and her offspring this year than in 1883.

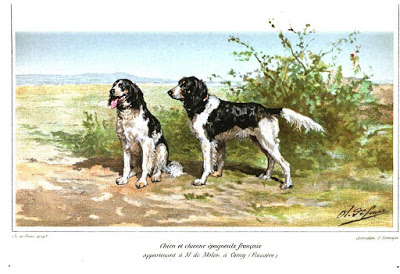

Our criticism didn't seem to have any effect since Odett and her offspring are still registered as French dogs by the Kennel Club and are well on their way to creating a line of pseudo-French Spaniels. Recently, a portrait of Kroumir and Odett appeard in the Journal d'agriculture pratique with an explanation of their origins. Here it is verbatim:

In I855, Mr. Molon obtained a Setter from Scotland. It was entirely white with silky hair, very beautiful and remarkably good. He crossed that white Scottish dog with a beautiful black and white silky-haired bitch with bright tan markings on her cheeks and the same colour on the nose and paws. The bitch was from North America, where it had been bred by a captain, a friend of Mr. Molon.

Later a bitch from this cross was bred to a beautiful Setter from England, with the same colour coat as the dog from North America and most probably belonging to the Laverack breed, although it was white with large black spots and bright tan markings above the eyes, cheeks and legs. However it did not have the same sort of undercoat as the Laveracks. It is through judicious inbreeding among the first crosses that Mr. Molon established his breed, which is now as beautiful and as good as Odett and Kroumir.

From the foregoing we can only conclude that the alleged French Spaniels are in fact from various Setter crosses; yes, they have been in France for thirty years, but their origins are actually English. We will refrain from discussing their qualities or from criticizing Mr. Molon; he bred and kept good dogs and they did well. Ultimately he did what we recommend French breeders do: use good dogs where you can, but use authentic purebred Pointers and Setters and stick with them.

But somehow the products of all these crosses have become French because they were born here and we've become used to them. But they are not now and never will be French breeds of dogs, and we wish to remind the Judges of upcoming exhibitions, and the Kennel Club, that we must require purebred dogs, and not accept the unfortunate mixes we now have on hand.

M. DE TOURIGNY

Eventually the French pointing breeds did get their act together. Official standards were drawn up, clubs were formed and breeders learned how to keep their lines pure...more or less. Nowadays, the épagneul breeds of France are recognized for what they really are; national treasures, living works of art, created by dedicated French hunters from a bygone era.

Today, the Brittany and the French Spaniel are doing quite well, while others like the Picardy, Blue Picardy and (especially) the Pont-Audemer remain vulnerable. But in yet another twist to the story, the French breeds which were nearly wiped out by an invasion of British breeds 150 years ago now seem to be winning hearts in the UK.

British and Irish hunters are shooting over Griffons, braques and épangeuls in increasing numbers. There is even a club for the Picard, Blue and Pont-Audemer in the UK now and the first litters of Picardy and Blue Picardy pups were whelped this year. A litter of Pontos may soon follow. I guess the old saying 'what goes around, comes around' is true after all!

Stay tuned for more on the origins of the Picardy and Blue Picardy Spaniels. I've got some more great images and quotes from the sporting press of the late 1800s and early 1900s.

Enjoy my blog posts? Check out my book Pointing Dogs, Volume One: The Continentals

11 nous souvient alors d'avoir critiqué celle décision, en faisant remarquer que ces animaux n'avaient aucun des caractères typiques des Epagneuls français; ils faisaient songer à une dégénérescence de Setters anglais, suite de croisements ou de sélection insuffisants.

Cette année, ladite Odett, de nouveau exposée avec son fils Kroumir 11 et cinq chiots, a obtenu le rappel de son premier prix de 1883 et le premier prix d'élevage, toujours pour Epagneuls français. Nous nous sommes permis encore de ne pas trouver davantage cette année qu'en 1883 dans Odett et dans ses produits le type de l'Epagueul français.

Critique bien platonique, assurément, puisque voici désormais Odett, et tous ses Kroumirs, inscrits comme chiens français sur la liste des origines de la Société canine et parcheminés à la patte, prêts à faire souche de prétendus Epagneuls français. Ces temps derniers, le portrait. d'Odett et de Kroumir a été reproduit dans le Journal d'agriculture pratique, et une notice explicative de la gravure donne l'origine des deux chiens et de leur race.

Nous reproduisons textuellement : « En I800, 31. M. de Molon se procure un Setter écossais, entièrement blanc, à poil soyeux, très beau et remarquablement bon. Il croise ce chien écossais blanc avec une magnifique chienne épagneule à poil soyeux mais noire et blanche avec feu très vif aux joues et mouchetée de même couleur sur le nez et les pattes. Cette lice était originaire de l'Amérique du Nord, d'où elle avait été ramenée par un capitaine de vaisseau, ami de M. de Molon.

Plus tard une lice issue de ce premier croisement fut donnée à un très beau Setter venant d'Angleterre, de la même robe que la chienne venant de l'Amérique du Nord et appartenant très probablement à la race Laverack, bien que ce chien blanc avec grandes taches noires et feu vif aux-yeux, aux joues et aux pattes, n'eût point le fond de la robe traitée comme la plupart des Laveracks.

C'est grâce à des alliances judicieuses in and in entre les produits de ces premiers croisements que M. de Molon est parvenu à constituer la race, absolument confirmée, aussi belle que bonne, représentée par Odett et Kroumir. Après ce qui précède la conclusion se tire d'elle-même. Les prétendus Epagneuls français ne sont que des chiens provenant de divers croisements de Setters ; ce sont donc bien et dûment des chiens anglais élevés depuis trente ans en France, mais réellement d'origine anglaise.

Nous nous garderons bien de discuter leurs qualités, ni de critiquer M. de Molon; il a reproduit et conservé des chiens qu'il trouvait bons et s'en est bien trouvé. En définitive il a fait ce que nous conseillons aux éleveurs français:,se contenter de prendre son bien où on le trouve, c'est-à-dire de recourir aux reproducteurs authentiquement de race pure — Pointers ou Setters — et s'en tenir là.

Mais les produits de ces élevages, devenus français par la naissance, par l'habitat, ne sont pas et ne seront jamais ce que. l'on appelle des chiens de race française, et nous signalons tant à l'attention des Jurys de nos expositions à venir, qu'à celle de la Société canine, la nécessité d'exiger la production des origines, et la regrettable anomalie que nous venons de constater pièces en main. DE TOURIGNY