Breed of the Week: The Cesky Fousek

It wasn’t until I was in university that I learned that Bohemia is a region of the Czech Republic, a country with a fascinating history, rich culture and something especially appealing to a young university student: world-class beer. Years later, when I began the research for this book, I also learned that the Czech Republic even had its own breed of versatile gundog. That was all the motivation I needed to save my money for a budget flight to Prague. How could I resist the lure of an exotic land where history, culture, beer and gundogs awaited me?

HISTORY

|

| "Wasserhund" (water dog) From Der Vollkommene Teutsche Jäger |

Those who argue in favor of an ancient origin invariably quote a 14th century letter written by a nobleman named Vilem Zajic of Valdek:

In the year 1348, King Charles IV presented to the Margrave of Brandenburg, Ludwig, fine hounds known as Canis bohemicus for the Margrave’s hunting pleasure.The author’s use of the term Canis bohemicus (Bohemian dog) is considered proof that hunting dogs native to Bohemia existed at the time. However, Zajic makes no mention of their color, size, coat type or even the kind of hunting they were used for; they could have been tracking dogs or sighthounds or water dogs. It is unlikely, though, that they were true pointing dogs. In the mid-1300s, hunters still had to train their dogs to set or point for the net. The few dogs that did have a natural tendency to point were just starting to appear in Italy, Spain and southern France at the time. Nevertheless, we can assume that Bohemia was indeed home to some kind of hunting dog talented enough to warrant the attention of its great king.

Another frequently cited reference is found in a fascinating book,

Der Vollkommene Teutsche [Deutsche] Jäger (“The Complete German Hunter”). Written by Johann Friedrich von Flemming around 1724, this richly illustrated two-volume encyclopedia mentions rough-haired dogs from Bohemia used mainly for water work. However, once again, no other details are provided. Like Zajic of Valdek, Flemming was describing a type of dog, not a specific breed. By 1724, some of

the Bohemian dogs may have even had a natural inclination to point. Most, however, were probably still used as flushers and retrievers.

|

| "Barber (Barbet) or Water Dog" From Der Vollkommene Teutsche Jäger |

At the time, crossbreeding was still a fairly common practice among hunters who simply wanted a good hunting dog. So the Cesky Fouseks of the late 1800s were more of a type of dog than a pure breed. There was probably considerable variation among them in terms of appearance, but in general they must have had similar qualities as versatile gundogs and were much appreciated by Czech, German and Austrian hunters.

Depending on where they were bred, they went by different names. The Czechs used the term Český Fousek. In Germany, experts such as Dr. Hans von Kadich used Stichelhaar or Straufhaarige Hühner- hund and breeders such as Franz Bontant from Frankfurt, called them “Hessian Rough-beards”. Despite the different names in use, all agreed that the dogs came from the area encompassing Bohemia, Moravia, Brandenburg and Hesse.

The political upheaval of the early 20th century was particularly violent in Eastern Europe. For the Cesky Fousek, it was nearly fatal. As war raged across the region, breeding came to a standstill. At war’s end in 1918, the Austro-Hungarian Empire had ceased to exist and a new nation, Czechoslovakia, had been proclaimed. But the Fousek was nearly extinct.

In 1924, a new association was formed with the expressed purpose of restoring the breed, but there were very few dogs left. Even worse, due to massive importations of English Pointers, Setters, and German Shorthaired Pointers, the Cesky Fousek had been relegated to a sort of second-class status among hunters. Undaunted, the few remaining Fousek enthusiasts continued their efforts. When, in 1931, they drafted a new breed standard and enacted new breeding regulations, the Fousek seemed to be on the road to recovery. But in 1939, war once again broke out in the region, and the breed was dealt another devastating blow.

After the Second World War, efforts to revive the breed got under way once again. The association of breeders, which somehow managed to remain intact throughout the war, issued new guidelines for its members. The Cesky Fousek was to be bred only by and for hunters, and the top priority of all breeders should be to retain the excellent hunting abilities and character in their dogs. Due to the breed’s small population and narrow genetic base, crossbreeding to other breeds such as German Shorthaired and Wirehaired Pointers was permitted for a time. However, when Czechoslovakia joined the FCI in 1957, and the breed club sought recognition for the Cesky Fousek, the stud book was closed and the club was required to prove that they had at least three generations of “clean” lines, free of any foreign blood. The breed also faced strong resistance from the VDH (German Kennel Club). The Germans opposed the idea of recognizing a breed they considered to be genetically identical to the Stichelhaar.

It was not until 1964, after an in-depth report on the origins of the Cesky Fousek was submitted to the FCI and the club had finally met all the requirements for pure breeding, that the breed was officially recognized as pure and independent, and its standard, FCI No. 245, adopted. Today, the breed is still represented by a strong and dynamic club in its native land where approximately 500-600 pups are whelped annually. Breeders are also active in Slovakia, Austria, Germany, France, Holland, the US, Canada and New Zealand. Slowly, but surely, the word is getting out about the Cesky Fousek, and its reputation as a dynamic, cooperative gundog is growing around the world.

The breed's name is pronounced: CHESS-key Foe-sek (Foe rhymes with toe). Ceský means “Czech”. “Fousek” is derived from the Czech word fousy, meaning facial hair or whiskers, and refers to the breed’s prominent moustache and beard. Strictly speaking, Cesky Fousek refers to a male dog. A female is a Ceska Fouska (Chess-ka Foe-ska). The FCI translates the name as the Bohemian Wire-Haired Pointing Griffon.

If there is one thing we’ve learned after years of travelling to Europe to photograph gundogs, it’s this: breeders generally don’t live in downtown Paris, Madrid or Prague. In fact, many of them live so far off the beaten track that even our GPS unit has had to ask for directions.

Fortunately, Lisa and I speak French, and we can get by in Italian and Spanish. So, when we travel to France, Spain or Italy, we usually have no problem communicating with the locals. In Germany, the Netherlands and Denmark, we stick to English, and hope that the people we meet there don’t take offense when we mangle a few words in their native tongue. But as we planned our first trip to Eastern Europe, I realized that neither of us could even say “hello” in Czech, Slovak or Hungarian, and that the trilingual pocket dictionary we purchased wouldn’t be of much help beyond the train station. Clearly, we had to find an interpreter, an English-speaking local willing to spend several days driving across eastern Europe with a couple of dog-crazy Canadians. Thanks to an international gundog forum on the internet, I found the perfect person. Not only did she speak English, Czech and Slovak, she turned out to be just as dog-crazy as we are!

Hana Dufkova is a delightful young woman and an accomplished dog trainer. She accompanied us throughout our travels in the Czech Republic, Slovakia and Hungary. Her interpreting services were invaluable. By eliminating the language barrier, she helped us gain a deeper understanding of the cultures in which the versatile dogs of the region were developed.

In the field, the Fouseks reminded me of the Stichelhaars and German Wirehaired Pointers I’d seen in Germany.They covered the ground at a medium gallop at a close to medium range. Without exception, they were very well trained. This was obvious when we began to take some retrieving photos. All of the dogs made happy deliveries of whatever their owners asked them to fetch. Even the biggest and stinkiest fox tossed into the forest was handled easily. At the water, we watched as several dogs were sent in for retrieves. There were no breakneck leaps into the pond, but there was no hesitation either —just a workmanlike effort to get the job done.

After spending an enjoyable day with members of the breed’s parent club, I began to realize that the Cesky Fousek is a lucky breed. It is firmly in the hands of a well-organized group of dedicated hunters, and its fortunes are on the rise outside of its native land. But I still had one more expert to interview. He had been unable to attend the meeting at the clubhouse, but had agreed to meet with us the next day at his clinic north of Prague.

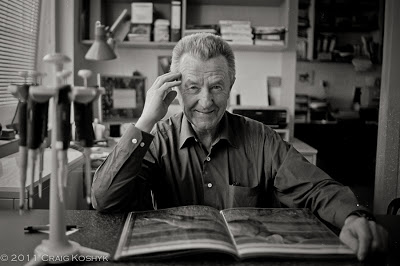

Dr. Jaromir Dostal is considered one of the world’s leading authorities on the Cesky Fousek. A geneticist by profession, he supervised the program designed to maintain the breed’s genetic diversity. But that’s not the reason I mention him here. I mention him because of something Lisa and I said to each other — simultaneously —after our interview with Dr. Dostal.

“Did you see his eyes?”

It was a look we had seen before; a certain fiery sparkle, a radiant glow on the faces of a handful of men we had met in our travels. They were men with decades of experience who had spent countless hours in the fields with their dogs. They had each dedicated much of their lives to a breed of gundog that, without their help, may have fallen into the abyss. We saw the years of ups and downs etched into their faces, and would sometimes hear notes of sadness as they spoke to us about the struggles they’d endured. But, when the light was just right, and the conversation turned to the great dogs they had known, they became young men again, their eyes transformed by an inner glow, their faces beaming.

We saw that look in Dr. Dostal’s eyes that day. Since then, I remember it every time I think about the Cesky Fousek, a lucky breed, indeed.

|

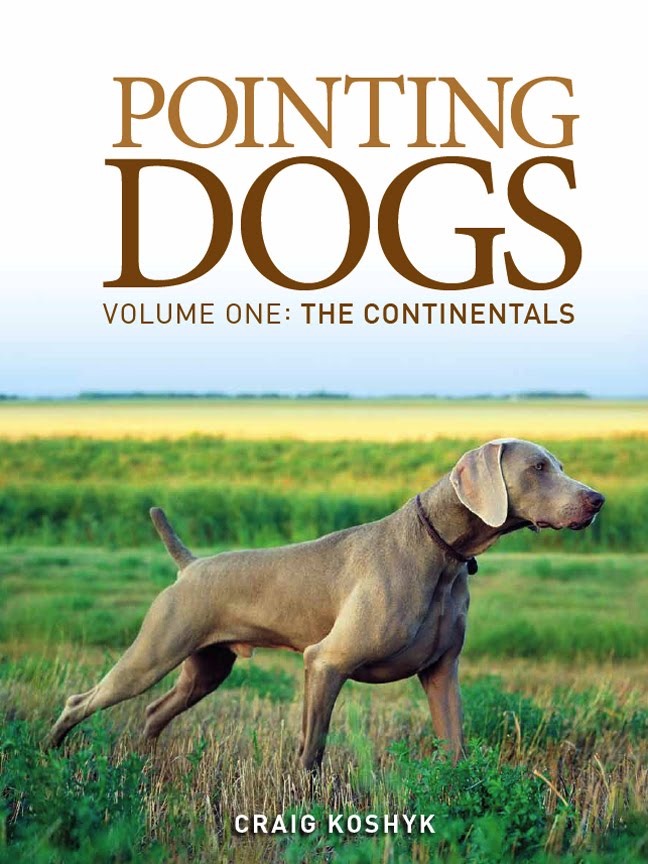

| Dr. Jaromir Dostal 1940-2010 Read more about the breed, and all the other pointing breeds from Continental Europe, in my book Pointing Dogs, Volume One: The Continentals |