It was established in 1997 and was made available on the Web in 2012. Anyone with access to the net can consult the over 2 million documents in the collection and I must admit that I visit the site at least once a day and sometimes squeal like a kid in a candy shop when I find something really interesting...like THIS:

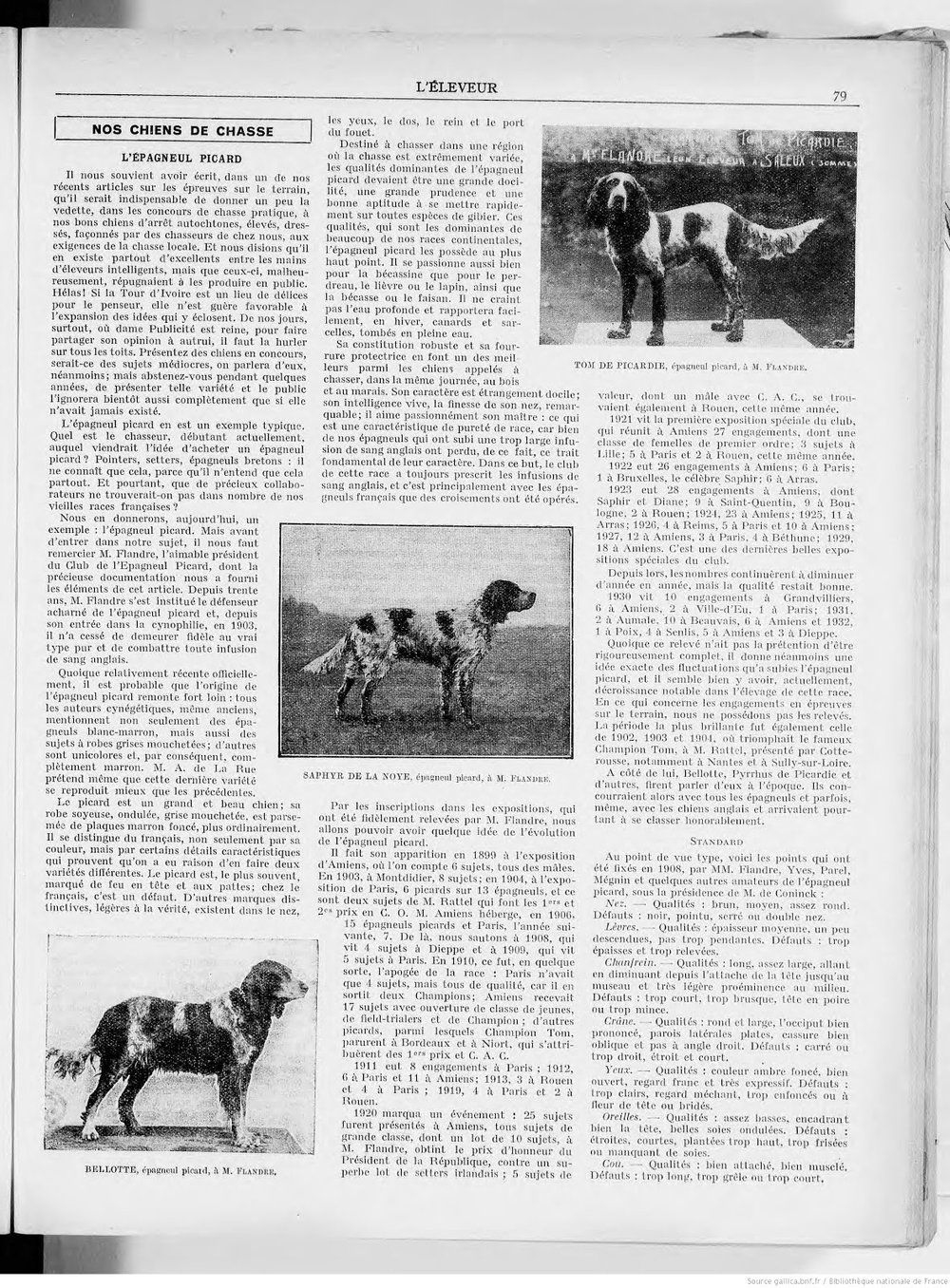

" It is description of the Picardy Spaniel's situation at the time and a detailed version of the breed's (then) standard. Here is the original (click to view full size). I will include an English translation below:

We recall having written, in one of our recent articles about field trials, that we should pay more attention to the field trials results of our outstanding native breeds of pointing dogs, bred by and for our own hunters to work in our conditions.

And we mentioned that there were excellent dogs just about everywhere in the hands of intelligent breeders, but that those breeders were, unfortunately, reluctant to promote them to the public. Alas! If the Tower of Ivory is a palace of delight for a thinker, it is hardly conducive to the sharing of the ideas that are formed there. Nowadays, especially, where mass marketing is King, in order to get the word out, you have to shout from every rooftop. When you present your dogs in competition it doesn't matter if they are mediocre, at least people will talk about them. But if you avoid showing your breed in public for a few years people will completely forget about it, as if it had never existed.

The Picardy Spaniel is a good example. Where would a hunter who is just starting out get the idea of buying a Picard spaniel? He's only ever heard of Pointers, setters and Brittanies because that is all he sees everywhere. And yet many of our old French races are full of excellent hunting partners.

So today, we will give you and example: the Picardy Spaniel. But before we get to our subject, we must thank M. Flandre, the amiable president of the Club de l'Epagneul Picard, whose precious documentation helped us write this article. For thirty years Mr. Flandre has been as the relentless supporter of the Picardy Spaniel, and ever since his entry into the dog world in 1903, he has remained faithful to the true and pure breed type, always rejecting any infusion of blood English.

Although it has only been officially recognized recently, it is likely that the Picardy spaniel's origins go back a long ways since all the classic hunting authors, even ancient ones, mention not only white and brown épagneuls but also one with speckled gray coats, ones that are self-colored and some that are completely brown. Mr. A. de la Rue even claims that the latter variety reproduces better than the preceding ones.

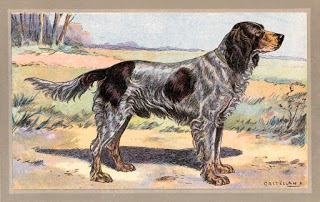

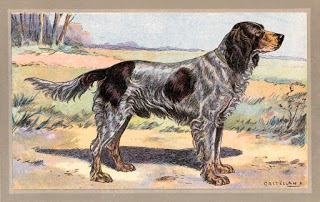

The Picard is a large and beautiful dog. Its silky, wavy, speckled gray robe is dotted with dark brown patches, more of the time. It differs from the French Spaniel not only in terms of coat colour but by certain characteristics that confirm the decision to separate the two different varieties was correct. The Picardy has, more often than not, tan markings on its head and feet, which for the French Spaniel that is a fault. Other distinctive markings, even though they are quite small exist in the nose, eyes, back, kidney and tail set.

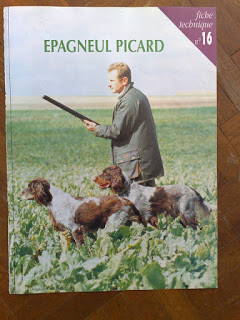

Developed to work in a region where hunting is extremely varied, the qualities of the Picardy spaniel should be great docility, a careful way of working and and the ability to quickly adapt to any kind of game. These qualities, which are the strong points for many of our continental breeds, the Picardy Spaniel has in abundance. It loves to hunt snipe, grouse, rabbit, as well as woodcock or pheasant. It does not fear the deep water and will easily retrieve waterfowl from the water, even in winter.

Its robust constitution and protective fur make it one of the best breeds for hunting the marsh and forest on the same day. It has a very docile nature, lively intelligence, excellent nose. It is devoted to its master, and that is a characteristic of racial purity since many of our spaniels have had excessive infusions of English blood and have lost that fundamental character trait. That is why the Picardy breed club has always proscribed infusions of English blood, so most of the crosses done in the Picardy where with French spaniels.

Statistics for the numbers of dogs shown in exhibitions, faithfully submitted by M. Flandre, give us some idea of the evolution of the Picardy.

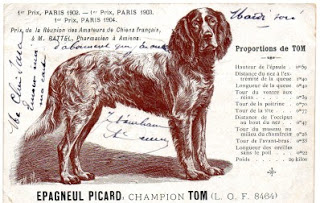

The first appearance was in 1899 at an exhibition in Amiens, where there are 6 dogs, all of them males were shown. In 1903, at Montdidier, eight; In 1904, at the Paris exhibition, 6 picardies among 13 spaniels, and two M. Raltel subjects made the first and second prizes in C. 0. In 1906, Mr. Amiens harbored 15 spaniels from Picardy and Paris, the following year, 7. From there, we jump to 1908, who lives 4 subjects at Dieppe and 1909, who lives 5 subjects in Paris. In 1910, it was, in a way, the apogee of the race: Paris had only 1 subjects, but all of quality, because two Champions came out; Amiens received 17 subjects with class opening of youth, field-trialers and Champion; Other Picards, among them Champion Toin, pBy the inscriptions in the exhibitions, which have been faithfully pointed out by M. Flandre, we shall have some idea of the evolution of the Picard spaniel.

He made his appearance in 1899 at the exhibition in Amiens, where there were 6 dogs, all of them males. In 1903, at Montdidier, eight dogs; In 1904, at the Paris exhibition, 6 picards on 13 spaniels, and two M. Raltel subjects made the first and second prize in C. 0. In 1906, 15 spaniels from Picardy Spaniels at Amiens and Paris, the following year, 7.

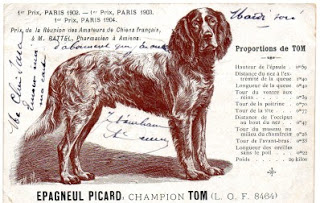

From there, we jump to 1908, 4 dogs at Dieppe and 1909, 5 dogs in Paris. In 1910, it was, in a way, the breed's apogee : Paris had only 3 dogs, but all of high quality, two Champions were made; Amiens, 17 dogs classes for youth, field-trialers and Champion; Other Picardies, among them Champion Tom, appeared at Bordeaux and Niort, who attended the first prizes and C. A. C.

1911 had eight entries in Paris; 1912, 6 in Paris and 11 in Amiens; 1913, 3 in Rouen and 4 in Paris; 1919, 4 in Paris and 2 in Rouen.

1920 marked an event. : 25 dogs were presented at Amiens, all dogs of high class, of which a lot of 10 dogs owned by M. Flandre, obtained the prize of honor of the President of the Republic, against a superb lot of Irish setters; Five very good dogs, including a male with C. A. C., were also in Rouen that same year.

1921 saw the first special exhibition of the club, which brought together at Amiens 27 dog including a class of first-rate females: 3 subjects in Lille; 5 in Paris and 2 in Rouen, that same year.

1922 had 26 dogs at Amiens; 13 in Paris, 1 in Brussels, the famous Sapphire, 11 in Arras.

1923 had 28 dogs at Amiens, including Saphir and Diane; 9 in Saint-Quentin, 9 in Boulogne, 2 in Rouen; 1921, 23 in Amiens; 1925, 11 in Arras: 192G, 4 in Reims, 5 in Paris and 10 in Amiens; 1927, 12 in Amiens, 3 in Paris. 1 in Béthune; 1929, 18 in Amiens. This is one of the club's last special exhibitions.

1930 saw 10 engagements at Grandvilliers, 6 at Amiens, 2 at VilIe-d'Eu. 1 in Paris; 1931, 2 in Aumale, 10 in Beauvais, 6 in Amiens and 1932, 1 in Poix, 1 in Senlis, 5 in Amiens and 3 in Dieppe.

Since then, numbers have continued to decline year after year, but the quality has remained good. Although this survey does not pretend to be thoroughly complete, it nevertheless gives an exact idea of the fluctuations of the Picard spaniel, and there seems to be at present a noticeable decrease in the breeding of this breed . With regard to field trials, we do not have the records. The most brilliant period was also that of 1902, 1903 and 1901, when the famous Champion Tom, to M. Ralttel, was presented by Cotterousse, notably at Nantes and at Sully-sur-Loire.

Beside him, Bellotte, Pyrrhus of Picardy, and others, made mention of them at the time. They would then compete with all the spaniels and sometimes even with the English dogs and yet managed to rank honorably.

BREED STANDARD

In terms of conformation, here are the points which were fixed in 1908 by MM. Flanders, Yves, Parel, Mégnin and some other supporters of the Picardy spaniel, under the presidency of M. de Coninck:

Nose - Qualities: Brown, medium, fairly round. Faults: Black, sharp, tight or double nose.

Lips - Qualities: Average thickness, somewhat lowered, not too pendent. Faults: too thick and too high.

Muzzle - Qualities: long, fairly broad, diminishing from the attachment of the head to the muzzle and very slight prominence in the middle. Faults: too short, too abrupt, head pear shaped or too thin.

Skull - Qualities: Round and broad, flat sides, oblique and not at right angles. Faults: square or too straight, narrow and short.

Eyes - Qualities: dark amber color, very open, frank and very expressive. Faults: Too light, wicked look, too sunken or or slanted.

Ears Qualities: well feathered, nicely framing the head. Beautiful wavy hairs. Faults: narrow, short, attached too high, too curly or lacking feathering.

Neck. - Qualities: well attached, well muscled. Faults: too long, too small or too short

Shoulders b- Qualities: fairly long, fairly muscular. Faults: Short, too straight, too oblique or too wide.

Limbs - Qualities: well muscled. Faults: too fine.

Chest - Qualities: deep, fairly broad, straight down to the elbow. Faults: too narrow not well down

Back - Qualities: medium length, slight depression after the withers, hips slightly lower than the withers. Faults: too long and roached.

Loin - Qualities: straight, not too long, broad and thick. Faults: too long, too narrow and weak.

Hips - Qualities: Prominent, arriving in the middle of the back and the loin. Faults: too low, too high or too narrow.

Croup - Qualities: very slightly oblique and rounded: the tail not attached too high. Faults: too oblique.

Flanks - Qualities: flat but deep, though fairly high. Faults: round, too high, too low.

Tail - Qualities: forming two slight curves, convex and concave, not too long, adorned with beautiful feathering. Faults: sabre too long or curly, attached too high or too low.

Front legs -. Qualities: straight, well muscled, elbows well let down, decorated with feathering. Faults: without feathering, fine, elbows in or out.

Back legs - Qualities: straight thighs, well let down, broad, well muscled, well fringed to the hocks, straight stifles, hocks slightly bent. Faults: narrow thighs, no fringes, bent or tight hocks.

Feet - Qualities: round, wide, tight, with a little hair between the toes. Faults: straight or flat or too open.

Skin - Qualities: fairly fine and supple. Fault: too thick.

Hair - Qualities: thick and not very silky, fine on the head, slightly wavy on the body. Faults: fine, silky, curly or too short.

Coat - Qualities: gray speckled, with brown patches on the various parts of the body and at the root of the tail, most often marked with tan points on the head and feet. Faults: too brown or white spots, or black.

Overall Powerfully built dog, from 55 to 60 cm at the withers, strong and lithe limbs, soft, expressive countenance, head carriage: lively and strong, strong well-developed front.

This wonderful breed, which is becoming more and more rare in exhibitions and which is no longer seen in field trials, must not be left to disappear. Let us wish for a triumphant awakening, like that of his first cousin, the French spaniel.

So how has the breed fared since 1933?

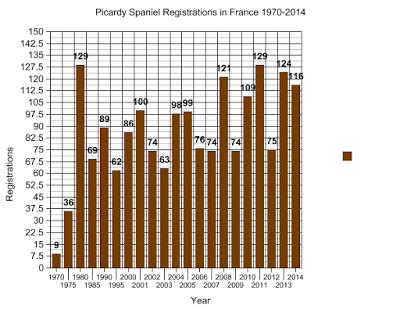

Throughout the 40s, 50s, 60s and well into the 70s, the number of Picardy Spaniel pups born in France was very low. Only 9 Picardy pups were registered with the French Kennel club in 1970 for example. Fortunately, since the 80s, numbers have risen and the breed has found the support of hunters in other countries. The chart below shows that average number of Picardy pups registered annually over the last 45 years is about100 pups, a tenfold increase from 1970, but still dangerously low.

Outside of France, stats are harder to come by, but my guess is that an additional 20 to 40 Picardy Spaniel pups are whelped in places like Germany, the Netherlands, the UK and Austria each year. So if the average life span of a Picardy is 9 years and there are say, 125 pups whelped per year, that means the entire world-wide population of Picardy Spaniels is only about 1000 individuals right now.

The numbers are better than they were in1933, but in a way, we are still waiting for the "triumphant awakening" the author of the article called for 85 years ago. And to be fair, we are starting to see light at the end of the tunnel. It looks like the number of pups being produced in France and elsewhere in Europe is on the rise and a few more hunters in North America are now getting into the breed. But there is still a lot of work to do so that "This wonderful breed... not be left to disappear."

Enjoy my blog posts? Check out my book Pointing Dogs, Volume One: The Continentals