I’ve previously written about Weimaraner pups being born with unusually large amounts of white in their coats, I called them ‘

Whitemaraners’. I noted that when photos of such pups are posted, most people automatically assume that the pups are cross-bred, the results of breeding a Weim to a Pointer or to a GSP. And they could be right…sort of. Weim crosses

can produce pups with grey and white coats or even solid grey coats

but only if they are done for at least two generations.

I don't think that there is any question that such crosses sometimes occur, either by accident or deliberately. But I had never really heard of anyone declaring them publicly...until now. Recently, on the Facebook page of a talented German photographer named

Anja Voss, an

album of photos appeared showing "Weimaranermix" pups. They are said to be 75% Weim, 25% GSP, ie: the offspring of a Weim and a Weim x GSP cross. The mix of coat colors in the litter is quite interesting. There are solid liver pups, solid grey pups, a liver and white pup and a grey and white pup.

So the bottom line as far as Weim crosses are concerned is that the DNA in

both parents must include a copy of the dilution factor responsible for the Weim grey coat color. In other words, if a pure GSP and pure Weim are crossed, the coats of all the pups simply

cannot be grey. They will be brown or black depending on the color of the GSP parent. None will be grey. However, if the GSP parent was not quite as pure as the driven snow, if for example it's a GSP x Weim cross, then it could indeed produce pups with solid grey or grey and white coats if it is bred to a pure Weim, or even if it is bred to another GSP x Weim cross, since both parents can contribute a copy of the dilution factor.

But what about those grey and white pups from other litters that the breeders swore up and down were from purebred parents? Are those breeders lying? Are Weim pups with white coats

always the result of cross-breeding no matter what the breeders say? Or is it in fact possible that pure Weim parents can produce such pups?

As mentioned in a

previous post, it has long been suspected that, yes, under certain circumstances, solid grey parents can indeed produce white and grey coated pups. Some geneticists have speculated that if the migration of melanocytes, cells that regulate coat color, is delayed or interrupted during the pups development in the uterus, the pup can end up having a lot of white in its coat at birth. But no one had been able to conclusively prove that theory. There was no smoking gun as it were. That is,

until now.

I can now report that conclusive proof has finally been established for pups with white and grey coats being produced by two solid grey parents. And it is now clear that the theory about disrupted melanocyte migration and proliferation is correct.

In a recently published paper entitled

Spotted Weimaraner Dog Due to De Novo KIT Mutation W.M. Gerding, D.A. Akkad & J.T. Epplen, the same team that examined the molecular genetics of the so-called

Blue Weimaraner, describe their investigation into the case of a Weim puppy with white spots born in Germany in a litter of otherwise normal-colored siblings. I recently interviewed Dr. Epplen about the investigation and the results.

Q: Dr. Epplen, tell me about how the project started.

A: About 2 years ago, a pup with a white spotted coat appeared in a litter of Weimaraners bred in Germany, not far from where I live. It was that breeder’s first litter and, as you can imagine, he was very surprised to see such a pup. His first thought was that it must be due to Pointer blood getting into the line somehow. But he had personally witnessed the mating of the two parents and was certain that his bitch had never been with a Pointer. So he contacted some more experienced members of the club and the breed warden, Mr. Giesemann and asked them for their opinion and advice. But when they saw the pup and the rest of the litter, they could not understand how it could have such a coat either so they contacted us to see if we could get to the bottom of it.

Q: So what sort of tests did you perform?

A: After collecting DNA samples from the pup, its parents and its siblings, the first thing we wanted to determine was the paternity and maternity of the litter. We wanted to know if the two dogs listed on the breeding documents were in fact the parents of all the pups. Within a week, we had the answer. The DNA clearly proved that the pups were indeed out of the two animals listed as parents.

Q: So you eliminated the possibility of the litter being a result of crossing to Pointers or GSPs?

A: Yes. The pup is a pure-bred Weimaraner, there is no question. Is is not the result of any cross breeding. Its parents are pure-bred Weimaraners from fully tested, recognized lines, approved for breeding by the club.

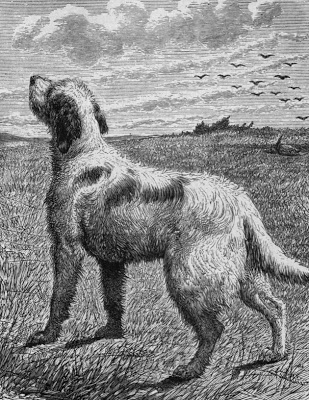

|

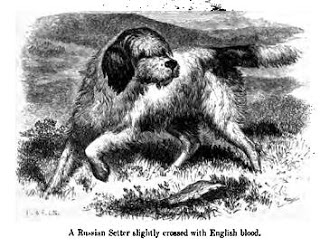

| Purebred Weim pups. The white coat is the result of a 'de novo' gene mutation. |

Q: So what tests did you run next?

A: The next step was to see if there were any mutations in the pup's genetic code that could be responsible for the white in its coat. So we ran DNA sequencing tests on a number of candidate genes that we know are associated with spotting in dogs. Eventually, we found a mutation. We identified it in a gene known as the KIT gene

*. Specifically, we found what is known as a

gene deletion, a missing portion of the DNA sequence in one very small area. And since the DNA of the parents and the solid-colored grey littermates did not have that deletion, we therefore concluded that the

piebalding in the pup’s coat was due to a

de novo (new) mutational event that occurred in that one pup’s DNA.

Q: So now that the pup has this new mutation, what would happen if it were bred? Would it produce pups with similar coats?

A: The trait would be transmitted in an autosomal dominant manner as we geneticists say. That means that if she were bred to another pure Weimaraner with a normal coat, any offspring would have a 50% chance of having a spotted coat and a 50% chance of having a normal Weimaraner coat as defined by the official standard.

Q: What about the parents of the white spotted pup? If they had another litter, would they have more pups with similar coats? The risk for the same breeding pair to produce another white coated pup would be negligible. In fact, they would have the same odds of producing more white pups as any other Weim in the world, less than one in a million.

Q: Have Weim pups with white coats ever been seen before in Germany?

A: The only evidence we have is anecdotal, but I am sure it has happened in the past. However, since white coats were thought to be evidence of cross breeding, or, at the very least a throw-back to Pointers in the Weim’s ancestry, they were hushed up. But in reality, there is always a certain statistical probability that this sort of thing can happen. If you breed enough dogs, you will eventually get this type of mutation. After all, every pup is born with several new mutations in its DNA. But since those mutations rarely result in something that is so highly visible, we don’t really notice them.

Q: What was the reaction of the breeder and of the club?

A: Obviously the breeder was relieved. He was ‘off the hook’ as it were and no longer suspected of allowing his bitch to be bred by a Pointer. It was somewhat of a hot-button issue in the official club since there are some members who would like to see any and all white markings eliminated from the breed, even the small white patches on the chest or toes which have always been in the breed and still occur from time to time today. But in the end it was decided that the affected pup would be registered and accepted as a pure Weimaraner, but not be allowed to breed. Her siblings on the other hand, provided they pass all the breeding tests, will not be forbidden to breed since they are pure Weimaraners and absolutely not affected by the same mutation.

* A gene that plays a role in the development of certain cell types, including the melanocytes that produce the pigment melanin found in the hair, eye, and skin. Mutations to the KIT gene can disrupt melanocyte migration and proliferation during development, resulting in a patterned lack of pigment knowns as piebaldism.