Breed of the Week: The Old Danish Pointer

Denmark is home to a classic breed of pointing dog with a unique look and interesting history. Virtually unknown outside its native land, the Old Danish pointer is represented by a small but dynamic club, and is still mainly bred by and for hunters.

History

History

Before I began my research into the Old Danish Pointer, I had assumed that the Spanish Gypsy dog story was true. But the more I looked into it, the more I began to have doubts. After all, the history of Gypsies in northern Europe is not exactly a study in social harmony and multi-culturalism. Digging deeper, the holes in the story became increasingly obvious. I now believe that the Spanish Gypsy dog story is probably a myth. Here’s why.

Gypsies first made their way to Denmark by ship in the early 1500s. They are said to have come from Scotland, where King James IV had given them a letter of safe passage to travel to Denmark, which was under the rule of his uncle, King Hans. Some sources suggest that the Gypsies had originally travelled to Scotland from

Spain, but no one knows for sure. What we do know is that other groups of Gypsies also moved into Denmark around the same time from what is now northern Germany, the Czech Republic and Romania.

By 1536, the political climate in Denmark had turned against the Gypsies. They were no longer allowed to enter the Kingdom, and those already there were given three months to leave. In 1589, the King decreed that any leader of a Gypsy band found on Danish soil would be put to death. As late as the mid-1800s, Gypsies were still being persecuted. The lucky ones were simply deported. But some were killed in organized “Gypsy hunts” in which “hunters” were given rewards for the capture, or even murder, of any Gypsy man, woman or child.

This organized persecution of Gypsy peoples began in Denmark a century before the Old Danish Pointer was even created, and continued throughout much of the breed’s development. How Gypsy dogs could have played any significant role with the Old Danish Pointer is hard to fathom. But somehow they have become part of the breed’s lore. Even the history section of the Old Danish Pointer’s FCI standard (

#281) mentions them:

The origin of the breed can be traced back to about the year 1710 when a man named Morten Bak ... through eight generations was crossing Gypsy dogs with local farm dogs and in this way established a pure breed of piebald white and brown dogs ...

|

| Morten Bak |

Personally, I believe the whole Spanish Gypsy dog story needs to be taken with a very large grain of salt. There are just too many holes in it to be plausible. But the Old Danish Pointer does look like a

Spanish Pointer, and it does point. So, what did Bak use to create it? To find the answer we need to consider the historical context of the time and examine a common thread found in many breed histories: war.

From 1701 to 1714, much of Europe, including Denmark, was involved in a conflict now known as the

War of Spanish Succession. A so-called Grand Alliance made up of English, Dutch and Austrian armies set out to prevent the French Bourbon king from taking the Spanish throne. There were significant battles in Spain and the Netherlands. From 1704 to 1709, Danish auxiliary troops fought alongside the Austrian army in some of those battles.

Morten Bak lived very near a number of important Danish ports where soldiers and sailors would have disembarked upon their return from battle. Some of them may have brought Spanish dogs back to their homeland. After all, there is little doubt that English soldiers did exactly that when they returned to England from Spain after the war. So, I believe that Morten Bak probably did use Spanish dogs. But he did not get them from roving bands of Gypsies. He would have found it much easier to get them from Danish soldiers returning from the War of Spanish Succession sometime after 1709. By crossing them to local hunting dogs, he would eventually create at a type of dog that earned the name

Bakhund (Bak Dog). It is not known for how long he continued to breed his Bakhunde, nor how far they spread during his lifetime, but by the mid-1800s, aided by the writings of poet

Steen Steensen Blicher, the breed’s popularity began to rise. The following is Blicher’s own description of what the dogs looked like at the time:

Morten Bak lived very near a number of important Danish ports where soldiers and sailors would have disembarked upon their return from battle. Some of them may have brought Spanish dogs back to their homeland. After all, there is little doubt that English soldiers did exactly that when they returned to England from Spain after the war. So, I believe that Morten Bak probably did use Spanish dogs. But he did not get them from roving bands of Gypsies. He would have found it much easier to get them from Danish soldiers returning from the War of Spanish Succession sometime after 1709. By crossing them to local hunting dogs, he would eventually create at a type of dog that earned the name

Bakhund (Bak Dog). It is not known for how long he continued to breed his Bakhunde, nor how far they spread during his lifetime, but by the mid-1800s, aided by the writings of poet

Steen Steensen Blicher, the breed’s popularity began to rise. The following is Blicher’s own description of what the dogs looked like at the time:

The size is more varied than in any other breed. There are huge dogs like bull-biters, small ones like spitz dogs, and short-haired, long-haired, single-nosed and cleft-nosed dogs. We reject the black ones, because the breed is not pure, and because they are difficult to see at a distance on the moors. ... So the best ones left for use are the white ones (either all white, or, which is most common, with brown color on the ears and head) and the piebald that is with brown specks all over the body.

Some sources claim that in the 1860s a number of Old Danish Pointers were sent to Germany where they contributed to the development of the German Shorthaired Pointer. Naturally, such claims are mainly from the Danish side of the border. I have yet to come across a single German source that confirms them. However, the first time I saw an Old Danish Pointer, I immediately thought of the early photos of German Shorthaired Pointers that show them as heavier and shorter of leg than they are today. Considering the close proximity of the two countries, and the fact that they went to war — twice— over the areas of Schleswig and Holstein in the mid-1800s, it is reasonable to assume that the Old Danish Pointer and the German Shorthaired Pointer could have contributed to each other’s development in the early days.

In any case, by the beginning of the 20th century, it was clear that the German Shorthaired Pointer was growing by leaps and bounds and that the Old Danish Pointer was in decline. The Second World War reduced the population even more, threatening its very survival. After the war, an effort to restore the breed got underway. A

breed club was established in 1947, and its members initiated an organized breeding program. By the 1960s, the population had increased significantly, and in 1963 the Old Danish Pointer was added to the official list of the FCI’s Group 7 for Continental Pointing Dogs. In the 1980s, thanks to Danish television personality Poul Thomsen and his Old Danish Pointer named Balder, the breed became well known in its homeland. Marianne Harild Sørensen, a breeder of Old Danish Pointers, explains:

Poul Thomsen had a nature program on TV. The program always started with him sitting at his desk and Balder in a basket next to the desk. So everyone saw this nice, quiet dog that would just lie there. Needless to say, everyone wanted to have a dog like Balder, so the numbers of puppies whelped rose quickly to over 400 per year. On the one hand, it was a good thing. The breed got some publicity. But on the other hand, it was a total disaster. The breeding wasn’t controlled in any way. The quality of many of the dogs was not good. Poul Thomsen wasn’t a breeder so he is not really to blame, but he and Balder did have an effect on the breed.

Today, the Old Danish Pointer has a small but devoted following in Denmark. The population is relatively stable and the breed is in the hands of an active and well-organized parent club. There are also breeders in Sweden, Germany and Holland. Thankfully, the tendency among most of them is to select dogs based on their working abilities.

Today, the Old Danish Pointer has a small but devoted following in Denmark. The population is relatively stable and the breed is in the hands of an active and well-organized parent club. There are also breeders in Sweden, Germany and Holland. Thankfully, the tendency among most of them is to select dogs based on their working abilities.

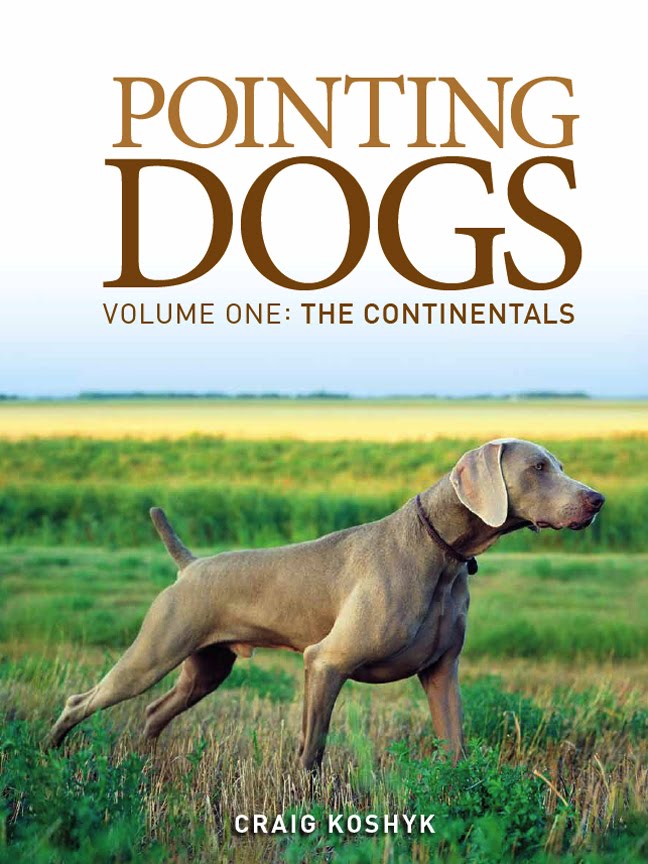

Read more about the breed, and all the other pointing breeds from Continental Europe, in my book Pointing Dogs, Volume One: The Continentals